A Mysterious Death: Metaphor and Science in Bleak House

What is the meaning of the gruesome death of an illiterate hoarder in Bleak House, and why did it lead to a fight between Charles Dickens and his friend George Lewes?

Two young men are waiting for a midnight meeting with an old shopkeeper. They are eager to examine secret documents in the shopkeeper’s possession.

One of the young men notices “a queer kind of flavour” pervading the neighborhood, like burnt chops that were not “quite fresh” even when first put upon the gridiron. The other becomes aware that smears of “black fat” have fallen on his coat sleeve and on the table. After touching the windowsill, one of them is startled to discover that his fingers are defiled with “thick, yellow liquor …, which is offensive to the touch and sight and more offensive to the smell.” It is a “stagnant, sickening oil … that makes them both shudder.” Then they realize that this substance “drips and creeps away down the bricks” outside the window forming a “thick nauseous pool.”

One of them goes to the appointed meeting place downstairs but returns, having found the shop empty. They try again together, finding the place still vacant save for a snarling cat, a “smouldering, suffocating vapour in the room [,] a dark, greasy coating on the walls and ceiling,” and “a crumbled black thing [] upon the floor.” As they continue to search the room for the documents, they suddenly realize that the “crumbled black thing” on the floor is the incinerated body of the old man they were expecting to meet.

What happened? Charles Dickens, the author of Bleak House, the novel in which this scene occurs, tells us that the old man died from “spontaneous combustion, and none other of all the deaths that can be died.”1

Hablot K. Browne, Frontispiece to Bleak House (1853).

Chancery and Corruption

Bleak House is structured around a Chancery Court case, Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, which has been in process for many years. Like other Chancery cases, the Jarndyce case devours not only the fortunes, but also the sanity, of the litigants. Dickens contrasts the “full dress and ceremony” of the court with the “waste, and want, and beggared misery” the court represents. Dickens adds that the Court of Chancery is “a bitter jest, [] held in universal horror, contempt, and indignation, [and] known for something so flagrant and bad that little short of a miracle could bring any good out of it to any one.”2

Mr. Krook, the old man who meets his end so singularly, is the sinister and perpetually intoxicated proprietor of a shop containing secondhand bottles, rags, bones, metalware, clothing, human hair, and law books, among many other things. The shop is within the shadow of Lincoln’s Inn, where Chancery lawyers, including the Lord Chancellor himself, have their chambers. In that lawyerly neighborhood, Krook is a living metaphor: he is referred to as “the Lord Chancellor” and his shop, the “Court of Chancery” because he has “a liking for rust and must and cobwebs.” His shop is crammed full of junk, including “old parchmentses and papers,” all of which are “wasting away and going to rack and ruin.” Like the judicial Lord Chancellor, Krook “can’t abear to part with anything I once lay hold of … or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me.” After Krook’s charred remains are found, the narrator exclaims that this death by spontaneous combustion is “the death of all lord chancellors in all courts and of all authorities in all places under all names soever, where false pretences are made, and where injustice is done.”3

Unlike his judicial doppelganger, Krook is illiterate, although he had been trying to teach himself how to read so that he could make sense of his “parchmentses.” His efforts are unsuccessful, and he dies without ever knowing the meaning of the papers he has been hoarding, just as the case Jarndyce v. Jarndyce burns itself out without reaching any meaningful conclusion. The entire estate at issue in Jarndyce is consumed by the cost of the litigation, leaving the minds and souls of the litigants like the cold embers of a spent fire. Krook’s death by spontaneous combustion befouls the entire neighborhood, just as Chancery litigation befouls and degrades all who encounter it.

John Atkinson Grimshaw, “Reflections on the Thames, Westminster” (1880). The Chancery Court is held at Westminster.

Lewes and Dickens: Fact, Intuition, and Fiction

Krook’s greasy, gruesome death was, for Dickens, an atypical foray into magical realism. Or so at least some readers thought, disapprovingly. Shortly after publication of the serial issue containing Krook’s death, George Henry Lewes (the common-law husband of George Eliot and soon to be former friend of Dickens4) criticized the scene as a “vulgar error” and “only admissible as a metaphor.” Lewes went so far as to call for Dickens to “avow a mistake” and admit the unreality of spontaneous combustion.

Dickens did no such thing; instead, he responded by insisting loudly that spontaneous combustion was a true scientific fact.5 Thus, in the preface he wrote for the novel’s release in book form (after the serial issue was released and after Lewes’s letter), he responded to Lewes’s criticism by characterizing it as “quite mistaken” and citing historical cases. He also asserted, defensively, that he would not “wilfully or negligently mislead my readers.” Yet he ended the preface with the non sequitur that “In Bleak House I have purposely dwelt upon the romantic side of familiar things.”6

Dickens could have argued that Krook’s death was a metaphor – and that Lewes’s criticism was, therefore, inapposite. But it seems to have been important to him that spontaneous combustion be accepted as scientific fact, just as it was important to Lewes to demonstrate that Dickens had erred. Lewes and Dickens debated the point in public and private letters with an intensity that seems inexplicable from a 21st century perspective – why did they care so much?

For Dickens, the answer lies in the relationship between intuition – the form of knowing that he privileges above all others in his writing – and fact. Dickens’s stories are full of intuitive leaps that prove more reliable than empirical understanding.

The case for the priority of intuition can be made without going beyond the pages of Bleak House itself. Esther, the first-person narrator for portions of the novel, is someone who depends on intuition above all other faculties. She senses the true identity of one character who has gone to enormous lengths to conceal it; she sees right through the freeloader who is imposing on Mr. Jarndyce, her guardian; she intuitively understands the evolution of the relationship between her two fellow wards. Mr. Jarndyce is also an intuitive thinker: he grasps the corruption and waste engendered by the lawsuit that bears his name on an emotional basis, rather than through rational consideration. When he is troubled about it, he attributes his unease to the “east wind.” The most interesting flash of intuition, though, strikes Mr. Bucket, a detective who is hired to solve a murder (yes, there are all different kinds of death in Bleak House). Instead of believing in the guilt of the obvious suspect, Mr. Bucket is struck by a revelation that his own lodger is the murderer: “By the living Lord it flashed upon me, as I sat opposite to her at the table and saw her with a knife in her hand, that she had done it!”7

Brooke Taylor argues that “for Dickens, the world of material facts must correspond with the world of intuitive understanding because the latter is what connects people to one another and gives facts their meaning and significance.”8 Essentially Taylor argues that Dickens’s worldview demands some consonance between feeling and fact, intuition and science. I would go a step further: for Dickens, empirical fact is necessary to confirm the priority and superiority of intuitive understanding. If intuition does not reveal factual truth, it loses its privileged position as the wellspring of human understanding and judgment. The “romantic side” of “familiar things” must be more meaningful than metaphor; it must confirm the truth of those familiar things.

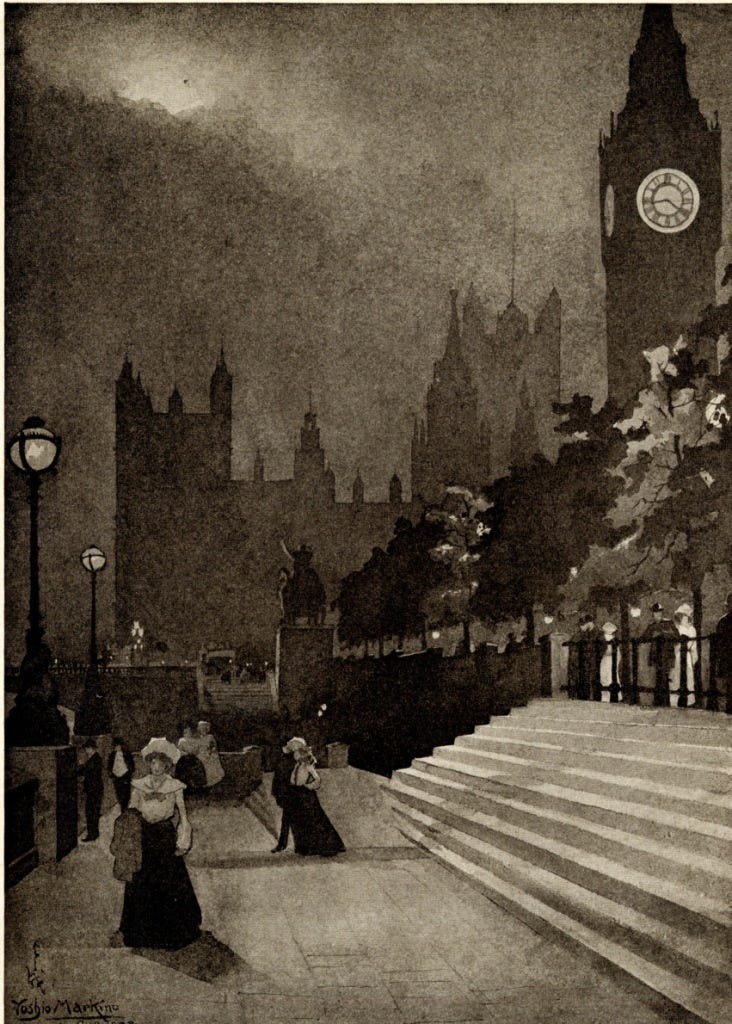

Watercolor by Yoshio Markino, date unknown. Image from Dave Walker, “Christmas days: a Markino bonus” in The Library Time Machine (December 23, 2015), available here. Markino was a Japanese artist based in London in the early 20th century. His illustration does a beautiful job of illustrating the fog that pervades Bleak House.

From Spontaneous Combustion to Alternative Facts

On January 22, 2017, we entered into a new social-epistemic paradigm when Kellyanne Conway defended assertions about the size of President Trump’s inaugural crowds against a charge that those assertions were “falsehoods.” Conway responded to this charge by saying that the assertions were not falsehoods, but “alternative facts.” Since then, it has become clear that we live in a world of “alternative facts” where X and not-X can both be true – to different and often hostile groups of people.

The world of “alternative facts” is completely alien to the earnest empirical debate that Lewes and Dickens carried out. Such a debate can only occur in a social setting in which the debaters agree that truth can be ascertained – and that it matters. We do not live in such a social setting now, which is, perhaps, why the spontaneous combustion debate seems so very quaint.

Hablot K. Browne, detail from serial cover for Bleak House (1852): Krook with his cat, attempting to learn his letters. Or is it Schrodinger’s cat?

All quotations thus far are from Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1853), ch. 32 (emphasis added).

Id., ch. 24.

All quotations in this paragraph are from Bleak House, chapter 5, except for the last, which is from chapter 32.

The relationships among these three thinkers and writers are discussed in the following open-source essay, which also addresses the spontaneous combustion debate, including the lengthy exchange of letters: Rosemary Ashton, “The Hilda Hulme Memorial Lecture 1991: Dickens, George Eliot, and George Henry Lewes” (University of London, 1991), available here.

Dickens’s belief in the scientific truth of spontaneous combustion appears to have been genuine. Bleak House is not his only writing to refer to the phenomenon. I was just reading Martin Chuzzlewit, where, to my surprise, Dickens offhandedly refers to death by spontaneous combustion in chapter 11.

Bleak House, 1853 preface.

Mr. Bucket’s flash of insight is not the only time in which a detective solves a murder by intuition in Dickens’s writing: in Dickens’s short story “Hunted Down,” an insurance investigator intuitively grasps a man’s murderous nature by looking at his carefully coiffed hair, which is “elaborately brushed and oiled” and “parted straight up the middle … as if he had said, in so many words: ‘You must take me, if you please, my friend, just as I show myself. Come straight up here, follow the gravel path, keep off the grass, I allow no trespassing.’” “Hunted Down” is available here.

Brooke Taylor, “Spontaneous Combustion: When ‘Fact’ Confirms Feeling in ‘Bleak House,’” Dickens Quarterly 27:171-184 (2010).