More Than Entertainment: Teachings in the Victorian Novel

Do writers see themselves as mere providers of entertainment, or do they think that their work has some other, perhaps loftier purpose?

In my previous post, I argued that readers should read for the fun of it, not to achieve some other objective. In this post, I’ll consider the views of the novelists of the 19th century.

In the Victorian era, many writers – and critics – thought that books should do more than entertain. Anthony Trollope, one of my favorite authors, maintained that a storyteller should teach ethical behavior and, consequently, avoid immoral content. But Trollope recognized that people generally don’t read novels because they think that doing so is good for them; they read because it’s fun. So, Trollope wrote in his Autobiography, a novelist seeking to teach ethical conduct has to make the message entertaining: “The writer of stories must please, or he will be nothing. And he must teach whether he wish to teach or no.”1 The teaching extends even to matters of love (and implicitly, sex): “It is from [novels] that girls learn what is expected from them, and what they are to expect when lovers come; and also from them that young men unconsciously learn what are, or should be, … the charms of love.”2

Trollope was not the only Victorian novelist to believe that a writer of stories had a responsibility to teach rightful conduct. His most famous contemporary, Charles Dickens, did not explicitly discuss the purpose of literature as Trollope did, but his novels crusaded against social ills such as the Poor Laws, debtors’ prisons, and warehousing schools. Dickens also emphasized the burden of guilt that accompanies wrongful conduct: bad actors are punished in their own minds as well as by the civil authorities. Images of the victim’s body haunt the murderer Bill Sikes, for example, and Jonas Chuzzlewit, too, suffers under the weight of “murder on his soul, and its innumerable alarms and terrors dragging at him night and day.”3

George Cruikshank, detail from “Sikes’s Death” (serial cover, 1846):

A murderer coming to a suitably bad end

In adhering to the idea that a novelist should have a moral purpose in mind, Trollope, Dickens, and others were swimming with the current, and with their own commercial interests. Lending libraries such as Mudie’s – which refused to carry works of “objectionable character” – were a major channel of distribution for their books.4 Mudie found novels by the writer George Moore (among others) “objectionable” on moral grounds. Moore responded to Mudie’s rejection with a polemic in which he deplored “the censorship of a tradesman who, although doubtless an excellent citizen and a worthy father, [is] scarcely competent to decide … delicate and difficult artistic questions.”5 Moore’s class-based dig at Mudie (tradesmen were perceived as belonging to a class below the gentlefolk) implies that Moore was motivated by elevated artistic considerations, not commercial concerns – although Moore’s loud protests suggest that he was sorely disappointed at being omitted from Mudie’s catalog.

Moore was not alone in objecting to the notion that novels should avoid “immoral” content. Thomas Hardy, another of my favorite authors, also protested what he referred to as “the censorship of prudery.” Hardy asserted that the principal distribution channels for novels -- magazine serialization and the circulating library – improperly excluded subjects central to “the finest imaginative compositions since literature rose to the dignity of an art.” Under the constraints imposed by magazines and libraries, Hardy claimed, the great masterpieces of the past, from Greek tragedies to Shakespeare to Milton, would all be banned if written in the late 19th century.6

Does Art Thrive Under Constraint?

Today’s readers probably agree with Moore and Hardy – and with most novelists, artists, and filmmakers of the past hundred years – that the constraints of propriety are not conducive to the production of great creative works. Hardy saw three possible solutions: one was for some books to be published non-serially and only for purchase (and excluded from lending libraries); another was to confine serial publication of more artistic works to periodicals read mainly by adults; and a third, related idea, was to establish periodicals for “the middle-aged and old.”7

In essence, Hardy’s proposal was to adopt the strategy that prevails today: divide the audience into segments. The movie industry provides a good example. Early on, the industry subjected itself to the Hays Code, a set of standards designed to make movies acceptable to general audiences. After the demise of the Hays Code in the 1960s, the industry adopted a rating system (G, PG, PG-13 etc.) that excluded some viewers from content inappropriate for them while also encouraging the fragmentation of the industry’s productions into genres marketed to specific segments of the population.

The moralistic approach associated with broad dissemination of creative work seems quaint today. But it’s hard to dispute the excellence of the works created under the constraints of the motion picture code and the circulating library. It’s possible that these limitations fueled the creativity of some writers, filmmakers, and artists and contributed to the longevity of their work.8

One could even argue that the moralistic approach takes art more seriously than the niche-oriented approaches in which creators enjoy complete freedom within the cubbyhole of their genre. Trollope proclaims the power of writing when he asserts that a writer “must teach whether he wish to teach or no.”9 Contemporary creators who enjoy a freedom foreign to the Victorians seem unconcerned by the possibility that their works might have that kind of power. Presumably the creators of gory films see their productions as mere entertainment; that’s why they don’t worry that people might be inspired to violence by going to the movies.

What do you think is the purpose of literature and other creative work? Does it have real-world impact, or is it mere entertainment?

Detail from a fountain, Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Florence, Italy

Novels referred to in this post:

Anthony Trollope, Ayala’s Angel (1881). This is a late romantic comedy, and my favorite Trollope novel. It brings the marriage plot to a point of perfection. You can read a longer description of it that I wrote here.

Anthony Trollope, The Prime Minister (1876). This novel is the fifth in Trollope’s political novel series. It features a woman with stunningly bad taste in men and a prime minister who does not really want the job.

Charles Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit (1844). This novel focuses on a common theme in Victorian fiction: the way a rich person’s wealth corrupts potential spouses and heirs, and the pathologies developed by the rich person in consequence of that corruption. The novel features an American sojourn that gives full play to Dickens’s disdainful view of American values and manners and a murderer who is systematically hunted down by a clever detective.

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (1838). Dickens’s second novel was a broadside at the workhouses established by the 1834 Poor Law and is a very entertaining read. Regrettably, it includes the most pointed examples of the antisemitism Dickens shared with other English writers of his time – the villain Fagin, always described as “the Jew,” is a collection of distasteful tropes.

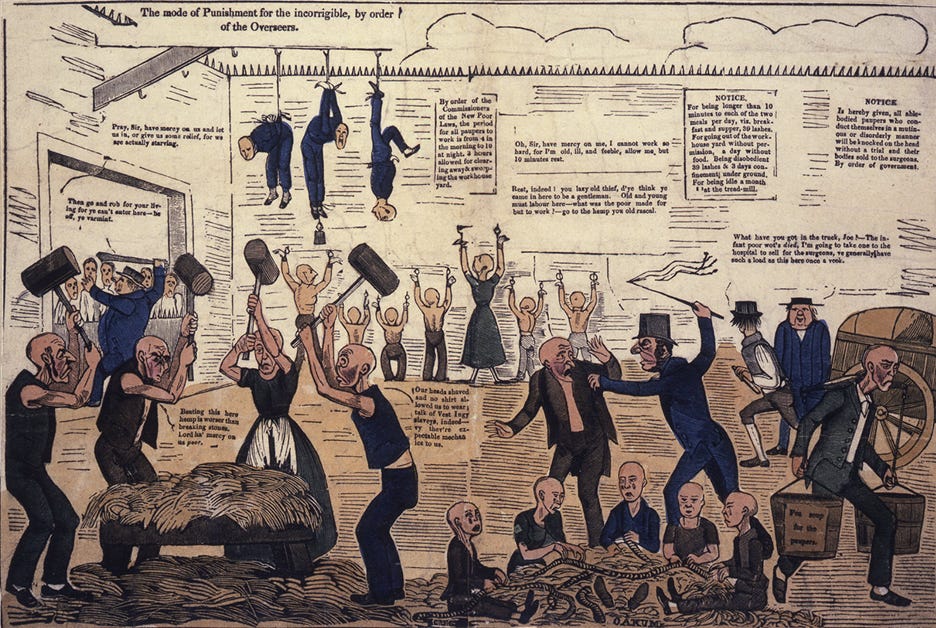

Below is a detail from an 1837 poster criticizing the Poor Law, which should give you some idea of why the Poor Law was very deserving of the criticism to which Dickens and many others subjected it. If work requirements for Medicaid recipients are imposed, history will be repeating itself.

Anthony Trollope, An Autobiography (1883), ch. 12 (emphasis added).

Id.

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist (1838), ch. 48; Martin Chuzzlewit (1844), ch. 51. Sikes escapes the punishment of the law by accidentally hanging himself.

Mudie’s was such an institution that Trollope repeatedly refers to it in his own novels. For example, one of the losses suffered by Lucy Dormer as she is taken in by poor relations after being orphaned is the lack of access to Mudie’s (Ayala’s Angel, ch. 2). When Ferdinand Lopez begins to require economy from his wife, he terminates her subscription to Mudie’s (The Prime Minister, ch. 47). There are many other examples.

George Moore, “Literature at Nurse, or Circulating Morals” (1885), pp. 3-4.

All quotations in this paragraph are from Thomas Hardy, “Candour in English Fiction,” New Review (1890).

Id.

Hardy may have agreed with this idea – hence his solutions, which would prevent certain segments of the general audience from having access to his work. Moore had no such compunctions.

I think there are three or more potential purposes. 1) entertainment; 2) teaching, which you describe as what is the right thing; and 3) developing empathy. To laugh is divine. To learn about how not to be a jerk is truly important and not obvious 😉. To learn about the human experience, what hurts, what brings joy, what causes anxiety, fear and dread is transcendent. To address the latter with depth requires, depending on the story, covering love, sex, illness, death, loneliness, jealousy, etc. The stories that have stuck with me over the years have given me empathy for the human condition.

An anecdote: I have a friend who, like me, is a widow. Unlike me she was also divorced. Though we both knew it wasn't a competition between the two states we found ourselves discussing which was worse. I was sure being a widow was worse. She said, "when you get divorced, no one brings you a casserole." Voila a story evoking empathy for the divorced. Neith entertaining not teaching per se, but enlightening.