"Poor Mr. Casaubon": Narratorial Guidance and Reader Judgment in Middlemarch

How do narrative techniques affect our judgments about characters we like or dislike?

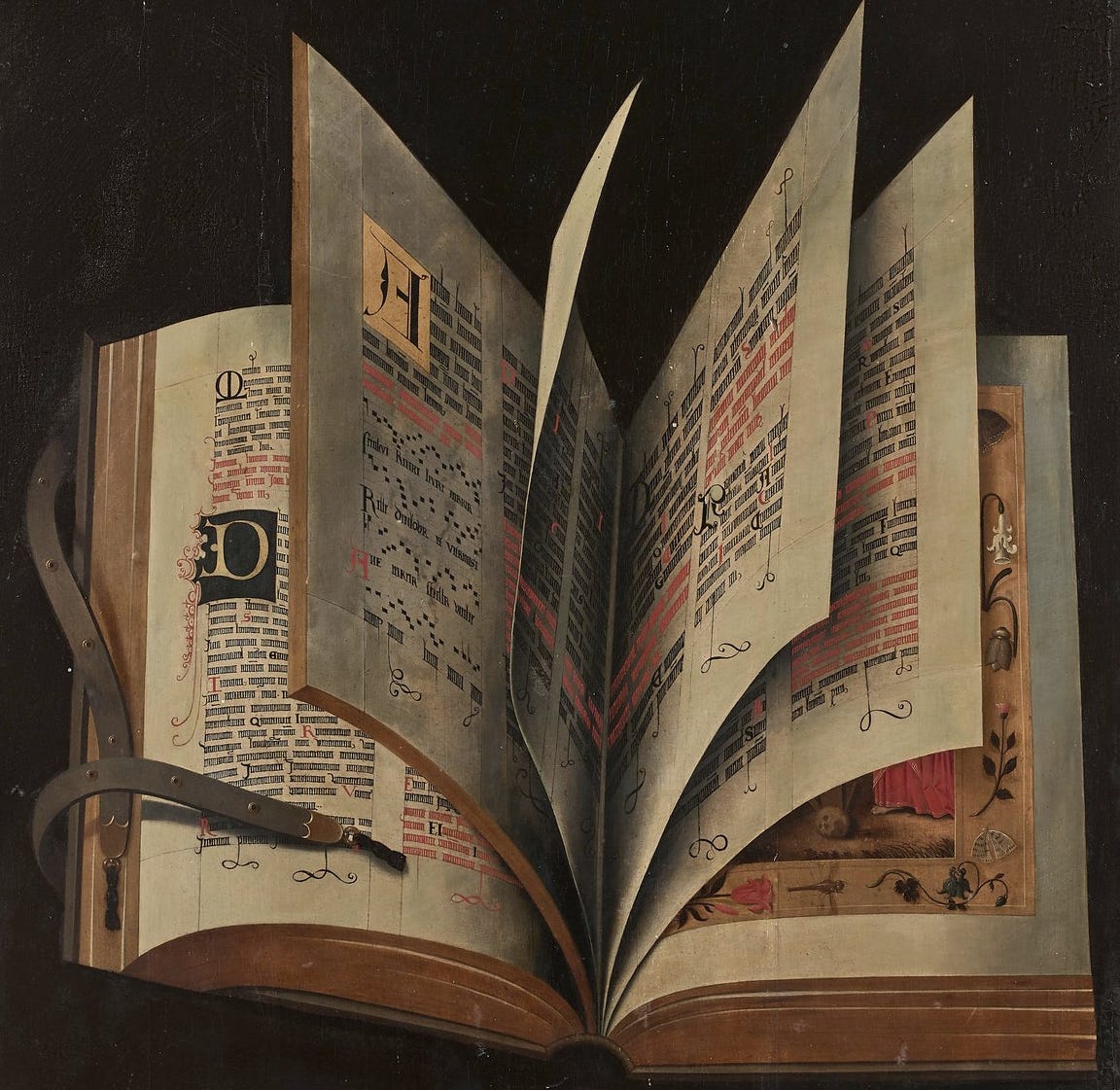

Starting to read a novel is like entering a new school for the first time. As you open the book and turn the pages, you want to understand who inhabits the world of the novel. Are there characters you will grow to love? Some who are treacherous? Some you will despise? You wish you had a guide, someone who could explain all the ins and outs: who the nice kids are, and the mean ones; what the teachers are like; what to avoid in the cafeteria.

In the 19th century novel, there is exactly this kind of guide: the narrator.

Each novelist has a distinctive narratorial voice. Jane Austen’s narrators are brief, witty, and gently sarcastic. Your Austenian guide to the school is a student who does not belong to any cliques, knows how to manage every teacher, and is so quick-witted and clever that no one would dare to bully her despite her habit of holding herself apart.

Trollope’s narrators are among the cool kids – but the cool kids who are kind, not mean. The Trollopian narrator understands the weaknesses of each student and can use that knowledge to advantage – but would never do so unfairly. They all respect him, although he does not stand apart. The Trollopian narrator also knows how to manage the teachers and can guide you around every unwritten rule. He knows the comfiest chairs in the library and how to smuggle in whatever snacks you want.

If you turn the cover of a George Eliot novel, your guide to the school is not one of the students, but the principal. She (or he) is wiser than you will ever be even if you live to be twice her age. She knows every subject better than the teacher who is supposed to be the expert in it. She knows all the languages taught at the school, and several more besides. She also understands the inner life of everyone in the school, from the nice students to the mean ones and from the inspiring teachers to the dull ones, and she will tell you about them. But don’t even think about comfy chairs or snacks.

Your guide in a Dickens novel is a cinematographer who is everywhere at once. He won’t explain anything to you, but he is always there, camera in hand, to capture the conversations between other characters and record each character in his most ridiculous moments—including moments in which the character occupies an apparently empty room.

Advancing into the 20th century to James Joyce’s Ulysses, you find not a person, but a sphinx behind the cover. If you are so clever as to get past the first sphinx, you will find a phalanx of other sphinxes, each awaiting their chance to eat your inner organs, right down to your kidneys, if you fail to decode the riddles.1

More on Joyce at the end of this post.

The Narrator is the Most Important Character in the Novel

The narrator who guides you through the Victorian novel is not the same as the author. As J. Hillis Miller explained (using Thomas Hardy as an example), “The narrator, it needs hardly be said, is not the real Hardy. He is a voice Hardy invented to tell the story for him ….”2 Another commentator, on George Eliot: “[T]he narrator should not be identified with George Eliot herself ….”3 Additional support for the author/narrator distinction in Eliot arises from her extensive use of epigraphs, which differentiate the authorial voice from the narrator’s.4 Lastly, Eliot’s and Trollope’s narrators often embed themselves in a fictional scene that the writers themselves couldn’t possibly experience, thus clarifying that the narrator has a separate persona. For example, Trollope writes, “It was amusing to see the positions, and eager listening faces of these well-to-do old men.”5 Trollope himself was not sitting among these fictional old men; his narrator was.

Because the narrator is so influential, many readers will feel persuaded to adopt the narrator’s judgment about other characters when that judgment is evident. A narrator can make it easy to love a character, but narrators also prompt the reader to form negative opinions about a novel’s less appealing inhabitants.

This post concerns the narrative techniques involved in illuminating the consciousness of one unappealing character: the Reverend Edward Casaubon in George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Casaubon is an elderly cleric who marries the young heroine, the passionate, religious Dorothea Brooke. She agrees to marry him out of an ardent desire to participate in his life’s work, which she understands to be a great intellectual undertaking. She sees him as “a man who could understand the higher inward life, and with whom there could be some spiritual communion,” a “modern Augustine who united the glories of doctor and saint.”6 After the marriage, however, Dorothea realizes that her husband’s work is futile and that he lacks the capacity to accomplish his objectives; and their married life reveals him to be small-minded, insecure, unkind, and jealous.

The narrator chronicles Dorothea’s bitter awakening to her husband’s smallness of character and intellect and directs our judgment as readers while the novel progresses. The narrator does this in three principal ways, which are interwoven within the novel. She (I will assign a female persona to this narrator, almost at random) exposes various characters’ mental judgments about Casaubon to the reader; she illuminates Casaubon’s own thinking to us; and she speaks directly to the reader with her own assessments.

Other Characters Judge Casaubon

As the narrator describes how other characters see Casaubon, she does not purport to use the words the character would use. Instead, she interprets the consciousness of the character in her own words. In explaining Dorothea’s initial delight in her then-prospective husband, the narrator says that “almost everything he had said seemed like a specimen from a mine, or the inscription on the door of a museum which might open on the treasures of past ages.”7 The narrator here tells us something about both Casaubon and Dorothea: in Casaubon’s case, that he is a scholar of antiquities, and in Dorothea’s case, that she longs for knowledge.

By the time the Casaubons are in Rome on their wedding tour, Dorothea’s views, as interpreted by the narrator, have changed. Dorothea feels that “the large vistas and wide fresh air which she had dreamed of finding in her husband’s mind were replaced by anterooms and winding passages which seemed to lead nowhither.”8 The spatial metaphors are the narrator’s, not Dorothea’s, even though the narrator is recounting Dorothea’s disillusionment.

Celia, Dorothea’s sister, makes no judgments about the validity of Mr. Casaubon’s intellectual objectives. Rather, she regards Mr. Casaubon’s studies as “a kind of damp which might in due time saturate a neighbouring body.”9 While the narrator here captures Celia’s sense that Mr. Casaubon’s learning could have unpleasant effects for Dorothea, she does so in narratorial language that does not originate from the prosaic Celia; it could even be understood as gently mocking Celia’s conventionality.

Casaubon’s Own Thoughts

The narrator employs a similar strategy in chronicling Casaubon’s own experience of courtship and marriage: she creates irony by describing his consciousness in language he would not have used.10 Thus, as Casaubon experiences a slight disappointment at what he expected would be the joy of his engagement, the narrator recounts his thoughts as follows: “[H]e determined to abandon himself to the stream of feeling, and perhaps was surprised to find what an exceedingly shallow rill it was…. [H]e concluded that the poets had much exaggerated the force of masculine passion.”11 Of course, readers know that this shallowness is the result of Casaubon’s own limited capacity for passion, not the limitations of “masculine passion” generally. We also know that Casaubon, in describing his own feelings, would not have used the water metaphors that the narrator employs so effectively.

Once married, Casaubon does not “f[i]nd marriage a rapturous state.” Rather, it is “a new pain” that the closeness of marriage is exposing his incapacities to his intelligent young wife, and he suspects that she is joining the “cold, shadowy, unapplausive audience of his life.” The narrator captures his sense of “betrayal” in the marriage: “the young creature who had worshipped him with perfect trust had quickly turned into the critical wife; and early instances of criticism and resentment had made an impression which no tenderness and submission afterwards could remove,” hard though Dorothea tries. Here again, the narrator sees Mr. Casaubon far more clearly than he could ever see himself. And the result here, as in several other places, is that the narrator resorts to pity: “Poor Mr. Casaubon!”12

The Narrator Delivers the Coup de Grâce

The narrator’s own judgments undermine whatever pity the reader might feel, however. The purely narratorial passages create a dialectic of sympathy and criticism that resembles Dorothea’s emotions during the marriage, but in the narrator’s judgments, criticism always seems to have the upper hand. An early remark about Mr. Casaubon’s pompous declarations of affection to Dorothea shows this dialectic: “No speech could have been more thoroughly honest in its intention: the frigid rhetoric at the end was as sincere as the bark of a dog, or the cawing of an amorous rook.” Thus, while granting Mr. Casaubon’s honesty, the narrator highlights his frigidity – a very apt verbal choice – and compares him to animals who act from instinct, not reason, i.e., not from intelligence, but from the constraints of nature. Later, the narrator piles on the animal comparisons by remarking that Mr. Casaubon “was as genuine a character as any ruminant animal.”13

At one point, the narrator suggests that the negative judgments of several other characters about Casaubon are unfair:

I protest against … any prejudice derived from Mrs. Cadwallader’s contempt … or Sir James Chettam’s poor opinion of his rival’s [Casaubon’s] legs … or from Celia’s criticism of a middle-aged scholar’s personal appearance. I am not sure that the greatest man of his age … could escape these unfavorable reflections of himself in various small mirrors ….

This allows the narrator to criticize the small-mindedness (“small mirrors”) of the many people who are scornful of Casaubon (while still memorably repeating their criticisms). But the narrator’s defense of Casaubon is half-hearted at best. It continues:

Mr. Casaubon, too, was the centre of his own world; if he was liable to think that others were providentially made for him … this trait is not quite alien to us, and, like the other mendicant hopes of mortals, claims some of our pity.14

So while the narrator observes that we all share Casaubon’s flaw of self-centeredness, she resolves the sympathy/criticism dialectic with an appeal to “our pity” (or only “some of our pity”) – as if Casaubon were a “mendicant,” a beggar. That comparison seems like a deliberate effort to highlight Casaubon’s weaknesses and limitations.

Other purported efforts to illuminate Casaubon’s point of view end in the same way. In the famous chapter opening in which the narrator begins with Dorothea but then interrupts herself (“Dorothea—but why always Dorothea? Was her point of view the only possible one with regard to this marriage?”), the narrator again defends Casaubon – while still focusing on his unattractive physical appearance: “In spite of the blinking eyes and white moles objectionable to Celia, and the want of muscular curve which was morally painful to Sir James, Mr. Casaubon had an intense consciousness within him ….”15 And then, after lingering on the unflattering descriptions other characters have made of Casaubon, the narrator sticks in the knife herself:

[Casaubon’s] soul was sensitive without being enthusiastic: it was too languid to thrill out of self-consciousness into passionate delight; it went on fluttering in the swampy ground where it was hatched, thinking of its wings and never flying. His experience was of that pitiable kind which shrinks from pity, and fears most of all that it should be known …. For my part I am very sorry for him.16

Pity again.

What are we to make of the narrator’s continual deployment of pity toward a man whose mind, the narrator says, “shrank from pity”? It is perhaps the ultimate judgment against Casaubon that the narrator’s generosity toward him goes no further than a pity that inspires contempt in the reader. The narrator asserts that we are all pitiably inclined, as Casaubon is, to consider ourselves “the centre of [our] own world.” Also like Casaubon, we are “born in moral stupidity, taking the world as an udder to feed our supreme selves.” Here, though, the narrator contrasts a likeable character, Dorothea, with Casaubon: Dorothea “had early begun to emerge from that stupidity” and had begun to recognize that Casaubon “had an equivalent centre of self, whence the lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference.” Casaubon’s inability or unwillingness to come to that same recognition, to flutter away from “the swampy ground where [his soul] was hatched,” is the flaw that inspires the narrator’s pity – and our contempt.17

More on Joyce

Here is the “more on Joyce” that I mentioned earlier: from the beginning of July until the middle of August, I’ll be taking a break from posting new essays weekly to study Joyce’s Ulysses. I will continue to post on a weekly basis, but some of the posts will be briefer and more impressionistic, and some of the posts will be slightly updated versions of earlier posts I did when I had fewer subscribers. Weekly posts will return in late August.

Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), likes to eat “the inner organs of beasts and fowls.” He especially likes “grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.”

J. Hillis Miller, The Form of Victorian Fiction Arete Press: 2d ed. (1979) p. 10.

K.M. Newton, “The Role of the Narrator in George Eliot’s Novels,” The Journal of Narrative Technique 3:97-107 (1973), p. 106.

David Leon Higdon, “George Eliot and the Art of the Epigraph,” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 25:127-151 (1970), p. 128; see generally J.R. Tye, “George Eliot’s Unascribed Mottoes,” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, 22:235-249 (1967).

Anthony Trollope, The Warden (1855), ch. 3; K.M. Newton, supra, p. 99; see generally Jeffrey M. Rothschild, “Renaissance Voices Echoed: The Emergence of the Narrator in English Prose,” College English 52:21-35 (1990).

George Eliot, Middlemarch (1871-72), chs. 2, 3.

Id. ch. 3.

Id. ch. 20.

Id. ch. 28.

James Wood, How Fiction Works, Picador: 10th anniversary ed. (2018), p. 9.

Middlemarch, ch.7.

Id. chs. 20, 42. Other noteworthy instances of “Poor Mr. Casaubon” occur in chs. 10 and 37. The narrator uses the expression “Poor X” for various characters in various situations, but with characters whose capacities for growth are limited (particularly Casaubon and Rosamond Vincy), it is very much an expression of pity shading into contempt. The narrator refers often to “Poor Dorothea,” but she does so in a way that makes the pity shade into sympathy and regret, not contempt.

Id. chs. 5, 20.

This quotation and the previous one are from Middlemarch ch. 10.

Id. ch. 29.

Id.

Id. chs. 42, 10, 21, 29.

I warmed to this essay right away because of the evocative comparison at the start. Then, the rest reminded me of the book in almost a sensory way. Thank you!

Hi Claire,

This post was put as a link on the Closely Readings page where a bunch of us are doing a slow read of Middlemarch so this excellent essay was timely and very informative. Have you ever thought of hosting a slow group read yourself? I think you would be excellent at it from a brief look at your posts 😊