Predators at Home: Not-Cinderella Stories from the Sherlock Holmes Canon

Some of Sherlock Holmes's female clients find that their money is an impediment to marriage - but for an unexpected reason.

The Vanishing Bridegroom

A young woman meets a man at a ball. The woman’s stepfather disapproves of her going out, so she meets the man in secret when her stepfather is away. The man proposes; the woman accepts. They resolve to marry before the stepfather returns. The woman vows eternal fidelity.

On the morning of the wedding, the bride and her mother – who supports her daughter in her wedding plans – get into a two-seater hansom cab to drive to the church. The bridegroom takes the next cab. Both cabs draw up in front of the church, but nobody emerges from the bridegroom’s cab. The cabbie looks inside; it’s empty!

The Governess in the Blue Dress

A young woman is offered a position as a governess. The pay is more than double what she made before, but it comes with strange requirements: she must don an electric blue dress worn by a grown-up daughter of the family who has moved to America, and she must cut short her chestnut-colored hair.

She accepts the job and its strange requirements, first cutting off her hair. She is asked to don the dress and to sit near the front window of the house from time to time. She discovers that one wing of her new employer’s house is locked up, and the family has a vicious mastiff. Two weeks after her arrival, she unlocks a drawer and finds – a mass of cut-off hair that exactly matches her own! Shortly after that, she attempts to explore the locked wing but is discovered by her employer, who tells her that if she enters that part of the house again, “I’ll throw you to the mastiff.”

A Common Pattern of Financial Control

What’s going on with these women? They are some of Sherlock Holmes’s clients, and so we must rely on Arthur Conan Doyle, speaking in the voice of Watson, to reveal the common thread running through their not-Cinderella stories.

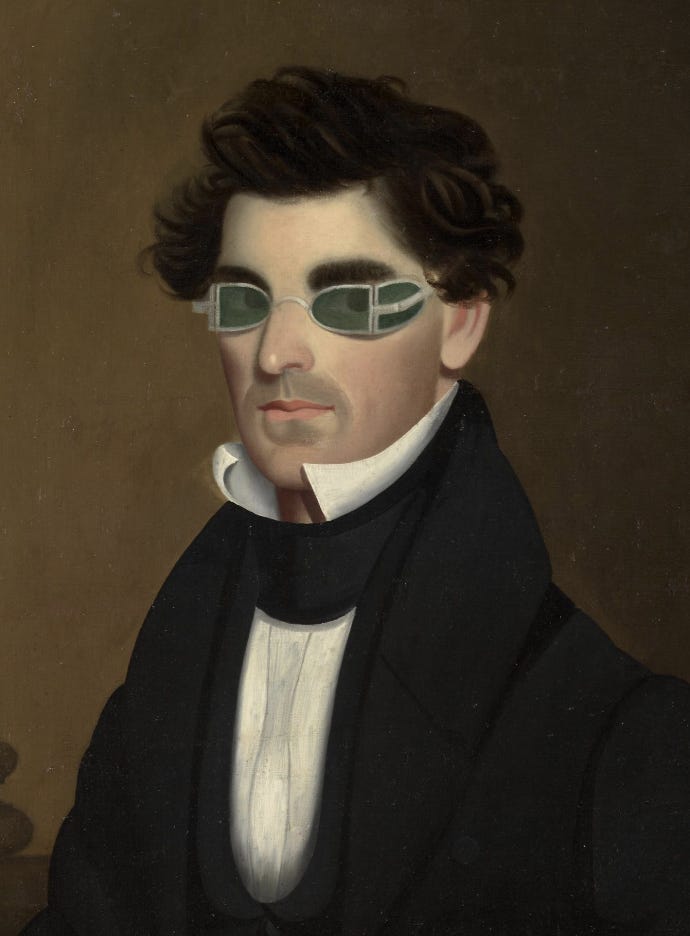

In the first case, “A Case of Identity,” Holmes’s client is Mary Sutherland, who wants to find her vanished fiancé, Hosmer Angel. While telling her story, she discloses that she has an income of her own that goes to her mother and stepfather for her maintenance while she lives at home. She recounts her meeting with Angel at the ball (a distinctly down-market affair with no princes or glass slippers; it was a “gasfitters ball”). She describes the missing man as speaking in a whispery voice, having bushy black whiskers, and having eyes that “were weak, just as mine are,” so that he always wears tinted glasses.1

Detail, Arthur Rackham, Aschenputtel at the Ball (1909). Mary Sutherland at the gasfitters’ ball was perhaps less ethereal than this, but one can always dream.

Holmes reasons – from the fact that the stepfather and Hosmer Angel are never in London at the same time, plus the appearance-related clues – that Angel is actually the stepfather in disguise. Here’s how Holmes explains his reasoning to Watson:

“The [stepfather] … enjoyed the use of the money of the daughter as long as she lived with them. It was a considerable sum, for people in their position, and the loss of it would have made a serious difference…. [S]o what does her stepfather do to prevent it? … With the connivance and assistance of his wife he disguised himself, covered those keen eyes with tinted glasses, masked the face with a moustache and a pair of bushy whiskers, sunk that clear voice into an insinuating whisper, and doubly secure on account of the girl’s short sight, he appears as Mr. Hosmer Angel, and keeps off other lovers by making love himself.”2

Detail of Jeptha Homer Wade, Nathaniel Olds (1837). Highly suspicious spectacles.

The second case is recounted in “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches.” Holmes’s client, Violet Hunter – the governess who is required to wear the blue dress – tells Holmes and Watson that once, while she was sitting by the window in her employer’s house, a man was observing her from outside the house. That aside, she is convinced that something is going on in one of the rooms in the shut-up wing of the house. Holmes puts all this together as follows:

“Of course there is only one feasible explanation. You have been brought there to personate someone, and the real person is imprisoned in this chamber. That is obvious. As to who this prisoner is, I have no doubt that it is the daughter … who was said to have gone to America. You were chosen, doubtless, as resembling her in height, figure, and the colour of your hair. Hers had been cut off, very possibly in some illness through which she has passed, and so, of course, yours had to be sacrificed also. By a curious chance you came upon her tresses. The man in the road was undoubtedly some friend of hers—possibly her fiancé.”3

Sidney Paget, “I took it up and examined it,” in Strand Magazine (1892). This is an original illustration from “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches” showing the discovery of the hair.

The impersonation is to convince the fiancé that the daughter is content without him. And the motive for imprisoning the daughter? As one of the servants of the house explains, the daughter “had rights of her own by will, but she … just left everything in [her father’s] hands.” So her father had something to lose financially if she married. Thus, “when there was a chance of a husband coming forward, who would ask for all that the law would give him, then her father thought it time to put a stop on it. He wanted her to sign a paper, so that whether she married or not, he could use her money.”4 She refuses, hence the imprisonment.

I won’t provide further spoilers – these stories are page turners and feature considerable action even after Holmes reaches his insights about what is happening to his clients. (The stories are available here.) But the stories provide an interesting counterpoint to Trollope’s heiresses who cannot be sure whether their suitors love them, or only their money (stories I discussed here). Holmes’s not-Cinderellas have the related problem that, because of their money, their parents do not want them to leave home, ever – which makes them more closely resemble Rapunzel than Cinderella.

A Game of Purses, not Thrones

Both forms of happily-never-after story shed light on the legal disabilities of women in 19th century common law, disabilities that were reinforced by prevailing social norms. As to married women (see my first post on not-Cinderella stories), “the very being or legal existence of [a] woman is suspended during the marriage” under the law of coverture.5

As to the principle more relevant to the Sherlock Holmes stories – a parent’s rights over the separate property of a female child – Blackstone’s Commentaries are less clear. Blackstone does say that parents have power over their children, “derived from … their duty; this authority being given them, partly to enable the parent more effectually to perform his duty, and partly as a recompence for his care and trouble in the faithful discharge of it.”6 In theory, this power terminated when a child came of age at 21, but by custom in England, middle and upper class women lived with their parents both before and after reaching the age of majority, providing a convenient mechanism for the parents to control and absorb their daughters’ property. It would have been highly unconventional – and would have subjected a woman to suspicion and disrepute – for her to establish a separate household for herself upon reaching majority, outside her parents’ protection.

The two stories I’ve featured here are not the only Sherlock Holmes stories that revolve around the legal manipulation of women for financial gain; Doyle, through the Holmes character, appears to have been keenly aware of the legal and social disabilities of women. Watson correctly characterizes Holmes as having “a good practical knowledge of British law.”7

Because Victorian women lacked sufficient legal authority to control their own property, 19th century fiction features not so much a game of thrones, as a game of purses. In a few weeks, I will take up Dickens’s macabre variation on this theme. Below the “share” button is more information on the Sherlock Holmes stories.

Brief Appendix on the Sherlock Holmes Canon

Between 1887 and 1927, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published four novels and dozens of stories featuring Sherlock Holmes and his sidekick Dr. Watson. If you have gotten out of the habit of reading, the stories are an excellent way to reestablish the habit – they are fast-moving and highly entertaining. The earliest set of stories, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, contains not only the stories discussed above, but also gems such as “The Red-Headed League.”

Sidney Paget, “I found Sherlock Holmes Half Asleep” in Strand Magazine (1891).

The Holmes Canon is interesting from a sociological perspective. The stories feature all classes, from the aristocracy to street urchins, and they are an excellent reflection of the complexities and perplexities of London at the turn of the century. They shed light on attitudes toward crime and the fear that it might be seething just beneath the surface of apparently tranquil London neighborhoods.

Holmes’s archenemy, Dr. Moriarty, is the embodiment of this unseen menace; Holmes describes him as “the Napoleon of crime …. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city.”8 The word “undetected” reflects the uncomfortable possibility that criminal activity might be present, yet invisible. The stories give the reader the sense that the scope of crime and evil in the city cannot be understood by ordinary means; much of it is imperceptible to ordinary citizens, yet it lurks around every corner. Reinforcing the sense of menace is the inadequacy of organized policing. Holmes criticizes the Scotland Yard detectives as “conventional – shockingly so,”9 and the stories are rife with their misjudgments and erroneous conclusions.

However dark and dangerous the city may be, in the Holmesian universe, the countryside is darker. In “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches,” the story of the governess discussed above, Holmes remarks, as he and Watson travel through the countryside:

“You look at these scattered houses, and you are impressed by their beauty. I look at them, and the only thought which comes to me is a feeling of their isolation and of the impunity with which crime may be committed there…. [T]he lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside…. The pressure of public opinion can do in the town what the law cannot accomplish. There is no lane so vile that the scream of a tortured child, or the thud of a drunkard’s blow, does not beget sympathy and indignation among the neighbours …. But look at these lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.”

Much of Victorian fiction takes place in villages and small towns, with London, Manchester, and other cities representing poverty, disease, class conflict, and other social ills. The Hound of the Baskervilles inverts these pastoral sensibilities, bringing darkness and terror to the countryside. As Watson approaches Baskerville Hall, he and his companions are confronted by a landscape that harbors both a spectral hound and an escaped murderer:

[B]ehind the peaceful and sunlit countryside there rose ever, dark against the evening sky, the long, gloomy curve of the moor, broken by the jagged and sinister hills…. Our wagonette had topped a rise and in front of us rose the huge expanse of the moor, mottled with gnarled and craggy cairns and tors. A cold wind swept down from it and set us shivering.10

Frederick John Widgery (1861-1942), Moorland Scene

A Note on the New Name

As you can see, this publication is now entitled “The Duck-Billed Reader.” That title stomped on the others in my poll from this post, garnering almost 60% of the votes, with “The Rag and Bottle Reader” coming in a distant second.

My friend and former colleague Christina Agapakis also kindly redesigned my duck-billed reader logo so that it’s more visible. She is a communications wizard who publishes Oscillator, an excellent Substack dedicated to issues of creativity at the intersection of biology and engineering. Check it out! In her most recent post, she has an interesting conversation with Claude, an AI, about feminist technology.

Arthur Conan Doyle, “A Case of Identity,” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892).

Id. (emphasis added).

“The Adventure of the Copper Beeches,” in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892).

Id. (emphasis added).

Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, Bk. I, ch. 15.

Id., ch. 16 (emphasis added).

Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet (1887), ch. 2.

Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Final Problem,” in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893).

A Study in Scarlet, ch. 3.

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), ch. 6.

very interesting.