Shriek, Roar, and Rattle: Trains as Engines of Doom in Victorian Fiction

Charles Dickens makes a convincing case that the railway is taking us into the inferno.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.1

This post will argue that the Victorians thought it would be fire: specifically, the world-eating fire of the emerging railway system. If you don’t think that the advent of railways sounds cataclysmic, read on and see if Charles Dickens can change your mind.

Caution: this post discusses suicide.

The industrial revolution comes to you

The first railway line in England opened in 1830. Railways soon proliferated, causing profound economic, environmental, and psychic disruption. The advent of the railroad altered temporal understandings of the world: railway timetables could only work when the “world of leisurely time” gave way to “a different view of time in which an iron schedule rules.”2 The growth of the railway also changed spatial understanding. The rail system linked the countryside to London, ripping apart the slow-moving world of the countryside with smoke, grime, noise, and industrial hazards.

In Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel Cranford, for example, the village ladies “vehemently petition[] against” the advent of the “obnoxious railroad.” Futilely, of course. And after it arrives, a much loved citizen is killed in a terrible accident. As explained by another local, the victim’s “foot slipped, and the train came over him in no time.“3

The railways exposed people who were far removed from factory work by geography or class to the thrum of the industrial revolution; the clangor and heat of machines so large they almost defied comprehension; and unprecedented sensations of speed, noise, dirt, and danger. These sensations led to a new focus on “the nervous effects of railway travel”; trains “represented the site of confrontation of the body and the forces of modernization.” Medical literature on railway accidents with their mass casualties and far-reaching traumatic aftereffects began to appear.4

Charles Dickens himself was an exemplar of the phenomenon of railway accident trauma. He was involved in a serious accident in 1865 at Staplehurst in which ten people were killed and many wounded when most of the cars of the train he was riding derailed and plunged into a riverbed. Although Dickens was not meaningfully injured, he described himself afterwards in numerous letters as “shattered” and “shaken,” and his family reported that in the years thereafter he exhibited “panic,” “fear,” and “terror” when riding on the railway.5

The mesmeric allure of the tracks: railways and suicide

The hypnotic power of the giant iron engines also inspired rail suicides. More than 10,000 rail suicides were recorded in England and Wales between 1852, when the first occurred, and 1949.6

Anthony Trollope’s novel The Prime Minister (1876) provides one striking example. The financially ruined speculator Ferdinand Lopez is left near the end of the novel with no way to redeem himself. He goes to the Tenway Junction railway station, where

the morning express down from Euston to Inverness was seen coming round the curve at a thousand miles an hour…. With quick, but still with gentle and apparently unhurried steps, he walked down before the flying engine—and in a moment had been knocked into bloody atoms.7

And then there is the terrible sadness of Anna Karenina’s despairing suicide:

And exactly at the moment when the space between the wheels came opposite her, she … fell on her hands under the carriage …. And at the same instant she was terror-stricken at what she was doing. “Where am I? What am I doing? What for?” She tried to get up, to drop backwards; but something huge and merciless struck her on the head and rolled her on her back…. And the light by which she had read the book filled with troubles, falsehoods, sorrow, and evil, flared up more brightly than ever before, lighted up for her all that had been in darkness, flickered, began to grow dim, and was quenched forever.8

The railway of the apocalypse

The apex of railroad-related Victorian fiction is Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son, a novel published in 1848, many years before Dickens’s traumatic experience at Staplehurst.

The railway comes up in several places in the novel. Early on, Dickens conveys the seismic impact of railway development in a neighborhood that is home to one of the working class characters. That neighborhood, Staggs’s Gardens, was “regarded by its population as a sacred grove not to be withered by Railroads”; the inhabitants are confident that their neighborhood would “long outliv[e] any such ridiculous inventions.”

But only a few years later, Staggs’s Gardens has “vanished from the earth.” In the area as reconfigured by development, railway time was

observed in clocks, as if the sun itself had given in…. To and from the heart of this great change, all day and night, throbbing currents rushed and returned incessantly like its life’s blood. Crowds of people and mountains of goods, departing and arriving scores upon scores of times in every four-and-twenty hours, produced a fermentation in the place that was always in action…. Night and day the conquering engines rumbled at their distant work, or, advancing smoothly to their journey’s end, and gliding like tame dragons into the allotted corners grooved out to the inch for their reception, stood bubbling and trembling there, making the walls quake …. But Staggs’s Gardens had been cut up root and branch.9

This is a fairly benign introduction to the railroad; the inhabitants of Staggs’s Gardens are no worse off, we find, except in the loss of their old neighborhood. But the next appearance of the railroad is not so innocuous. Mr. Dombey, bereaved after the death of his young son, goes on a railway journey.

The very speed at which the train was whirled along, mocked the swift course of the young life that had been borne away so steadily and so inexorably to its foredoomed end. The power that forced itself upon its iron way—its own—defiant of all paths and roads, piercing through the heart of every obstacle, and dragging living creatures of all classes, ages, and degrees behind it, was a type of the triumphant monster, Death.

The metaphorical comparison of the railway to death continues for several paragraphs of such power that they transcend prose, and I can do no better than quote them here.

Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, from the town, burrowing among the dwellings of men and making the streets hum, flashing out into the meadows for a moment, mining in through the damp earth, booming on in darkness and heavy air, bursting out again into the sunny day so bright and wide; away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, through the fields, through the woods, through the corn, through the hay, through the chalk, through the mould, through the clay, through the rock … like as in the track of the remorseless monster, Death!

Through the hollow, on the height, by the heath, by the orchard, by the park, by the garden, over the canal, across the river, where the sheep are feeding, where the mill is going, where the barge is floating, where the dead are lying, where the factory is smoking, where the stream is running, where the village clusters, where the great cathedral rises, where the bleak moor lies, and the wild breeze smooths or ruffles it at its inconstant will; away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, and no trace to leave behind but dust and vapour: like as in the track of the remorseless monster, Death!

Breasting the wind and light, the shower and sunshine, away, and still away, it rolls and roars, fierce and rapid, smooth and certain, and great works and massive bridges crossing up above, fall like a beam of shadow an inch broad, upon the eye, and then are lost. Away, and still away, onward and onward ever: glimpses of cottage-homes, of houses, mansions, rich estates, of husbandry and handicraft, of people, of old roads and paths that look deserted, small, and insignificant as they are left behind: and so they do, and what else is there but such glimpses, in the track of the indomitable monster, Death!

Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, plunging down into the earth again …. Away once more into the day, and through the day, with a shrill yell of exultation, roaring, rattling, tearing on, spurning everything with its dark breath, sometimes pausing for a minute where a crowd of faces are, that in a minute more are not; sometimes lapping water greedily, and before the spout at which it drinks has ceased to drip upon the ground, shrieking, roaring, rattling through the purple distance!

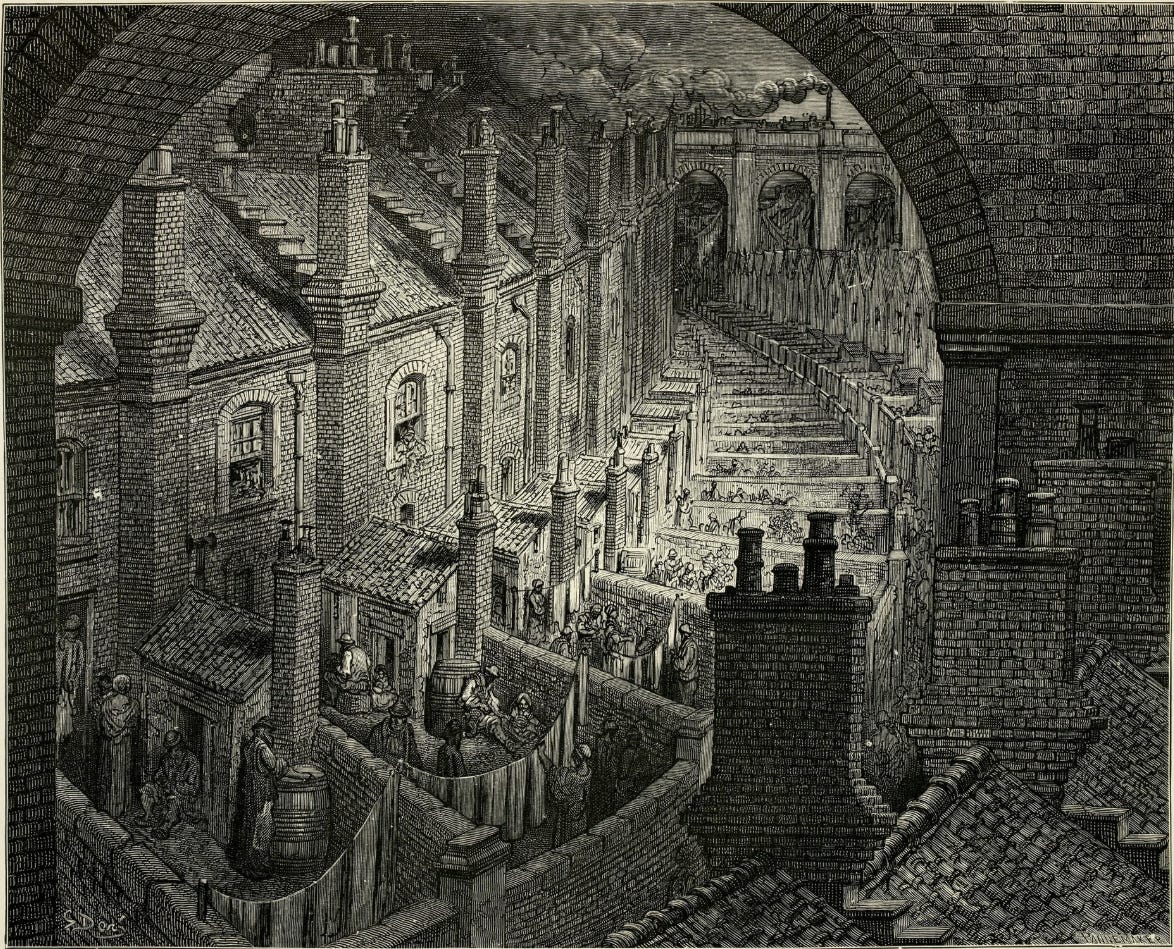

Louder and louder yet, it shrieks and cries as it comes tearing on resistless to the goal: and now its way, still like the way of Death, is strewn with ashes thickly. Everything around is blackened. There are dark pools of water, muddy lanes, and miserable habitations far below. There are jagged walls and falling houses close at hand, and through the battered roofs and broken windows, wretched rooms are seen, where want and fever hide themselves in many wretched shapes, while smoke and crowded gables, and distorted chimneys, and deformity of brick and mortar penning up deformity of mind and body, choke the murky distance…. It was the journey’s fitting end, and might have been the end of everything; it was so ruinous and dreary.10

This passage illuminates why the railroad is so revolutionary.

It has the inexorability of death, as each paragraph emphasizes.

It goes everywhere; nothing can escape it. It swallows whole neighborhoods, going “where the mill is going, where the barge is floating, where the dead are lying, where the factory is smoking” and many other places besides.

It is faster than anything ever seen before. “The very speed at which the train was whirled along, mocked the swift course of the young life that had been borne away so steadily and so inexorably to its foredoomed end.”

It is monstrously powerful, flying across the earth’s surface and beneath it as if burrowing through earth were effortless. Its power “force[s] itself upon its iron way—its own—defiant of all paths and roads, piercing through the heart of every obstacle, and dragging living creatures of all classes, ages, and degrees behind it”; “plunging down into the earth again … Away once more into the day, and through the day.”

It’s terrifyingly loud: “Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle …. Louder and louder yet, it shrieks and cries.” Underground it goes “booming on in darkness.”

It doesn’t move aside for anything or anyone; things in its path give way. That is why Staggs’s Gardens “had been cut up root and branch”; that is why it just goes through land masses in its way: “through the fields, through the woods, through the corn, through the hay, through the chalk, through the mould, through the clay, through the rock.”

It exposes the ugliness of English poverty: “There are jagged walls and falling houses close at hand, and through the battered roofs and broken windows, wretched rooms are seen, where want and fever hide themselves in many wretched shapes, while smoke and crowded gables, and distorted chimneys, and deformity of brick and mortar penning up deformity of mind and body, choke the murky distance.”

It burns and blackens like hell brought to the earth’s surface: “its way, still like the way of Death, is strewn with ashes thickly. Everything around is blackened.”

Near the end of the novel, Mr. Dombey is in angry pursuit of his former right-hand man, James Carker, who has betrayed him and attempted to run away with his wife. In an extraordinary chapter recounting Carker’s thoughts and feelings as he attempts to evade Dombey’s pursuit, Dickens never uses Carker’s name, only the pronoun “he”: Carker has been transformed into a nameless being, reduced only to fear. The chapter has the same kind of poetic rhythm as the passages I quoted earlier, but it focuses on the inexorability of pursuit in a way that makes Carker’s end seem as inevitable as the trains themselves.

After many sleepless nights of travel, he stops at an inn near a railway. There, he is terrified by a passing train:

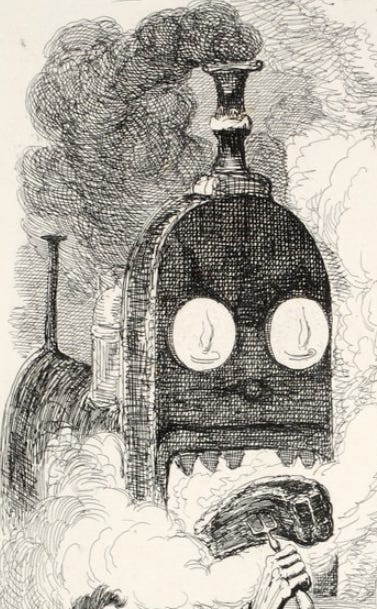

The ground shook, the house rattled, the fierce impetuous rush was in the air! He felt it come up, and go darting by; and even when he … saw what it was, he stood, shrinking from it, as if it were not safe to look. A curse upon the fiery devil, thundering along so smoothly, tracked through the distant valley by a glare of light and lurid smoke, and gone!

He is fascinated by the trains as they come rushing past.

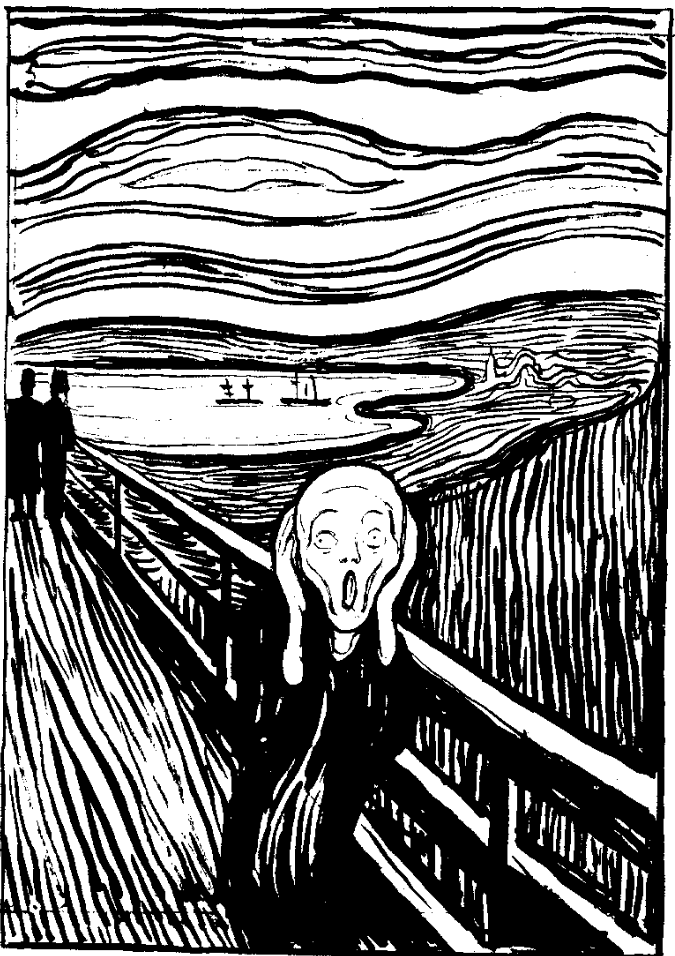

A trembling of the ground, and quick vibration in his ears; a distant shriek; a dull light advancing, quickly changed to two red eyes, and a fierce fire, dropping glowing coals; an irresistible bearing on of a great roaring and dilating mass; a high wind, and a rattle—another come and gone…

He is mesmerized as he watches a train that has stopped at the station briefly, “thinking what a cruel power and might it had. Ugh! To see the great wheels slowly turning, and to think of being run down and crushed!”

He returns to his inn but cannot sleep. He spends the night watching “the dull light changing to the two red eyes, and the fierce fire dropping glowing coals, and the rush of the giant” as train after train passes by. By the morning, “Death was on him. He was marked off—the living world, and going down into his grave.” Outside again, he sees Mr. Dombey running toward him.

He heard a shout—another … felt the earth tremble—knew in a moment that the rush was come—uttered a shriek—looked round—saw the red eyes, bleared and dim, in the daylight, close upon him—was beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air.11

So: the vision of the end is the burning, red-eyed iron dragon of the industrial revolution, a nightmare in motion, the railway apocalypse.

I’ll end here, with the hope that the looming cataclysms we fear today will someday seem as tame as railroads do now.

These are the opening lines of Robert Frost’s poem, "Fire and Ice" (1923). The poem in full is as follows:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

It’s interesting that Frost considers hate to be a species of ice. It doesn’t feel that way these days.

Murray Baumgarten, “Railway/Reading/Time: Dombey and Son and the Industrial World” in Dickens Studies Annual 19:65-89 (1990), p. 68; see generally Nicholas Daly, “Railway Novels: Sensation Fiction and the Modernization of the Senses” in ELH 66:461-487 (1999).

Block quotation and quotations in preceding paragraph from Elizabeth Gaskell, Cranford (1853), chs. 1, 2.

Daly, supra n.2, p. 468; see also id. at 469.

Id. at 461-62.

M. Clarke, “Railway suicide in England and Wales, 1850–1949” in Social Science & Medicine 38:401-407 (1994), abstract.

Anthony Trollope, The Prime Minister (1876), ch. 60.

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina (1878), Part 7, ch. 31 (Constance Garnett translation (1901)). Earlier in the novel Anna is present when a man is crushed to death by a train - not a suicide, but it is suggestive.

The passages about Stagg’s Gardens are from Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1848), chs. 6, 15.

All passages about Mr. Dombey’s railway journey are from Dombey, ch. 20.

All passages about Mr. Carker’s flight and demise are from Dombey, ch. 55.

Perhaps ICE is a species of hate?

Interesting as always. (I had not known about the accident Dickens himself experienced!) There's a train killing in Gaskell's North and South also. And as a sort of postscript one could mention Kipling's "Mrs Bathurst", written 3 years after Victoria's death, and eerily showing a train and cinema causing a man's death (though not directly.)