The Unwritten End: When Authors Die Before Their Characters

What does it mean when a character's narrative arc is cut short by the death of the writer?

Ivan Aivazovsky, Ship Off the Coast (1874), detail.

As I was working on my first post, researching the sensation surrounding the death of Little Nell in Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop,1 I came across an essay by Charles McGrath in the New York Times, “And They All Died Happily Ever After.” Cataloguing the many beloved characters killed off by their creators, from Little Nell to Sherlock Holmes to Rabbit Angstrom, McGrath suggests that there is a fitness about these literary killings. “In novels,” he explains, “poignant, untimely deaths are often better than long, drawn-out ones.”

Endings

McGrath’s point is that many writers feel a “wish for closure” for their characters. And of course, an author can create that closure in many ways. The marriage plot – so beloved in the 19th century – takes the characters up to the moment of marriage and then leaves them there, forever congealed in an aspic of wedding-day bliss. Anthony Trollope often pushed certain characters out the door without detailing their future lives (“Now the narrator will bid adieu to Mary Lowther”; “And with the same grey horses shall the happy bride and bridegroom be bowled out of our sight”; “On the next day Lily Dale went down to the Small House of Allington, and so she passes out of our sight.”).2

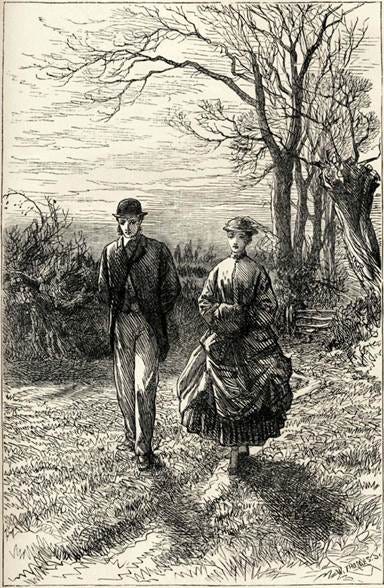

Illustration by G.H. Thomas for The Last Chronicle of Barset.

Trollope keeps these two characters forever on parallel paths that never meet; but he ends their stories.

A more conventional method for Victorian novelists to end their stories – and the narrative arcs of the characters – was to review the fates of the dramatis personae after the close of the events of the novel. Dickens ends his great novel Barnaby Rudge by tracking the progress of each of his characters to a satisfying endpoint. We learn of the happy lovers and the children later born of their marriage; the private secretary who turns spy and dies by taking poison; and the quarrelsome lady’s maid who becomes a turnkey at a women’s prison and is skilled at “inflicting an exquisitely vicious poke or dig with the wards of a key in the small of the back.”3

Un-ending

McGrath’s essay contrasts the satisfying closure resulting from the “poignant, untimely death” of certain characters with the unknown and unknowable fate of Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin, the lead characters in Patrick O'Brian’s 20-novel series. Jack and Stephen outlived their creator, who died at 85, three chapters into the 21st book. McGrath remarks that O'Brian “apparently wrote with no thought of neatly winding things up.”

O’Brian’s series, set during the Napoleonic Wars, covers the naval careers of a captain (Jack) and his friend, the ship’s surgeon (Stephen). At the point when O’Brian died, he had written his two protagonists into middle age. Jack had just been promoted to the rank of Admiral, and the two friends were comfortably ensconced, with their families, aboard Jack’s ship. O’Brian’s handwritten notes indicate that Stephen was about to win a duel and that a dinner party was about to occur. The characters and the plot are coiled up, full of potential energy – and consigned to permanent stasis by the “poignant, untimely death” of their writer.

Poignant indeed. I can’t clear my mind of the image of O’Brien writing on as his body failed, struggling to continue his characters’ narratives even as his own was ending.

As a young adult, I misunderstood my grandmother as she waxed gloomy about her future death. “I’m living on borrowed time,” she would sigh, referring to the fact that she had outlived her predicted actuarial life span. I thought that she was afraid of dying, and perhaps she was. But now that I have more life behind me than ahead of me, I can understand her gloom better. I don’t dread dying, but I do dread not living. And I can envision writing until the bitter end as a way of trying to stave off the bitterness, and perhaps even the end itself.

I’ll reflect on (and use naively) Decartes’s first principle, “Cogito ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”).4 Writing is a complex act of thinking, one that ex-ternalizes and e-ternalizes the writer’s thoughts. It projects the writer’s consciousness outward both interpersonally and temporally. If a writer casts her thinking into the world by writing, perhaps she creates a kind of existence, of not-ending, by virtue of having thought in a concrete, written form. Or perhaps that is simply her hope.

Alas, the characters who have outlived their author seem lost and bereft, no matter how comfortable they may be. As one of Pirandello’s titular six characters in search of an author explains, while “the writer, the instrument of the creation will die, … his creation does not die.” And unlike their author, the characters lack the power to create an ending. As the same Pirandello character complains, “Our reality doesn't change: it can't change! It can't be other than what it is, because it is already fixed forever.”5

Forever incomplete stories create a painful moment for the reader, as she comes to the end of the writing with no end to the story. And the most painful moment is the one in which she is forced to intervene to end the stasis: to effectuate an unsatisfying ending, very different from a “poignant, untimely death,” by closing the unfinished book and beginning the inevitable process of forgetting.

Zygmunt Andrychiewicz, The Dying Artist (1901).

Note that signs of the artist’s work are scattered about everywhere.

Appendix of Books Discussed or Quoted in this Post:

Note: I’ll be including an appendix like this after most posts - but it’s mainly for people who think that they might want to read some of the books. Here goes:

Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop. This is an early novel, interesting principally for its treatment of compulsive gambling – Little Nell and her grandfather are uprooted and left homeless because of the grandfather’s compulsion to make a fortune for Little Nell at the gambling table – and its diabolical villain, Quilp. Quilp is both a dwarf and Dickens’s most over-the-top villain. It’s worth reflecting on the ways in which Dickens sometimes creates characters who are both villainous and physically unusual; he seems to have had no consciousness of his own tendency to create a freak show, and no consciousness that creating one might be an act deserving of criticism.

Anthony Trollope, The Vicar of Bullhampton. This is a very interesting late novel in which Trollope’s typical marriage plot is only a subplot. The principal storylines relate to the vicar and his conflict with a local nobleman; and a murder, the young man who is suspected, and his sister, a “fallen woman.” I’m planning another post in which this excellent novel will play a large part.

Anthony Trollope, Ralph the Heir. This novel features love-and-money-related intrigue surrounding a squire and his nephew and heir, a much-disliked spendthrift. It contains some of Trollope’s most acerbic and beautifully written commentary on shallow, superficial people.

Anthony Trollope, The Last Chronicle of Barset. This novel wraps up Trollope’s six-novel series, The Chronicles of Barsetshire. Widely regarded as a masterpiece, it features Josiah Crawley, the learned, impassioned, impoverished, and depressed cleric who is accused of theft, as well as the love affair between his daughter and the son of a wealthy family. There are many subplots, including the unsuccessful wooing of a young woman by the suitor depicted in the illustration above. Although this novel continues stories begun in other novels, it can be read on a standalone basis, and I highly recommend it.

Charles Dickens, Barnaby Rudge. This is one of Dickens’s two historical novels, covering the Gordon Riots of 1780. If you’ve never heard of the riots, you will be surprised to learn how strikingly relevant they are to contemporary American politics. The scenes of mob violence feature some of Dickens’s most dramatic and moving writing. This novel is also distinguished by Dickens’s most varied and extensive stable of villains.

Patrick O’Brian, The Complete Aubrey/Maturin Novels. This is a series of 20 novels, plus an unfinished book posthumously entitled “21.” The first novel in the series, Master and Commander, is an entertaining lark but has subtly and beautifully developed characters; the second, Post Captain, features the Austenian marriage plot from a masculine perspective and is an excellent read on its own.

Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921). Pirandello writes a play into which six characters erupt, insisting on telling their story – a story that their author has deliberately suppressed. Because these characters are attempting to oppose the will of their author, they are not simply left to drift as Patrick O’Brian’s characters are. And indeed, despite what The Father says (he is the character I have quoted above), the characters are not adrift at all, nor do they succeed in opposing the will of their creator. In fact, they are within the firm grasp of their author, who has artificially created the sense that they have an existence and consciousness independent of himself. As one commentator explains, “Hiding and unseen, the author is watching all of them perform, and writing down his own play: The Six Characters in Search of an Author. It turns out that the poor stooges, while trying to enact their own suffering drama, have been used for a completely different purpose, one they do not and cannot suspect. Are we still to speak of ‘autonomy’ of the characters?” Antonio Illiano, “Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author: A Comedy in the Making,” Italica 44: 1-12 (1967), p. 7. And of course, Pirandello was very much alive when he wrote them into their predicament.

I am indebted to Kendall Dudley for the suggestion to discuss Six Characters in this post.

True confession: I was unable to find any primary source to support this story; it might not be true. Certainly, though, The Old Curiosity Shop was immensely popular, and Dickens was treated as an honored celebrity when he visited the United States shortly after its publication. (The visit did not go well – see Dickens’s American Notes.)

The Vicar of Bullhampton, ch. 71; Ralph the Heir, ch. 56. Last Chronicle of Barset, ch. 77.

Barnaby Rudge, “Chapter the Last.”

Decartes used this principle, which he articulated in several places and in different formats, to provide a foundation for knowledge against a backdrop of radical doubt on the question of being. Since the 17th century, philosophers have been debating the interpretation and application of this principle, often referred to simply as “the cogito.” I’m not going to wade into any of those debates. For my purposes, it is enough that the cogito accords with an intuitive grasp of existence and thought. Insofar as that intuitive grasp is inconsistent with Decartes’s original logic, take my use of it as simply the application of a naïve reading.

Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921) (Storer translation 1922).

I so much enjoyed this piece, and yet it seems odd, in a discussion of endings, to draw Patrick O’Brian, who gave us two fascinating lives to follow over the course of 20 volumes, into the same framework as authors faced with ending a single book. O’Brian may have left his characters dangling in the final, unfinished manuscript, but should we not celebrate him as a master of endings, who at the conclusion of volume after volume, artfully paused the lives of his two main characters in a way that satisfied readers, and yet left them longing to know more?

In literature I suppose a "poignant, untimely death" can represent closure. But in life an untimely death is forever the opposite. In writing the obituary of my first husband who died in middle age, I felt at least part of the purpose of the work was to make whole, that which was unfinished.