The Art of the Deal: Not-Cinderella Stories from Charles Dickens

In some of Charles Dickens's novels, the real players in the marriage market are the parents of the bride.

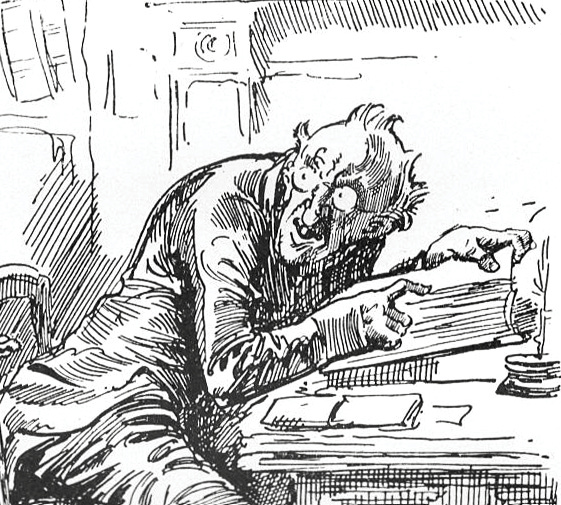

A young woman is about to be married. Her husband-to-be, Arthur Gride, is “a little old man, of about seventy or seventy-five years of age, of a very lean figure, much bent and slightly twisted…. His nose and chin were sharp and prominent, his jaws had fallen inwards from loss of teeth, his face was shrivelled and yellow ….”1

Harry Furniss, “The Wedding Feast,” in the Library Edition of Nicholas Nickleby (1910), detail. This illustration shows the bridegroom-to-be Arthur Gride at home and gives you a good sense of his attractions, or lack thereof. | This image and all Dickens illustrations in this essay come from Michael John Goodman, The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery, an invaluable resource.

Gride, on the other hand, describes his bride-to-be, Madeline Bray, as follows: “a young and beautiful girl; fresh, lovely, bewitching, and not nineteen. Dark eyes, long eyelashes, ripe and ruddy lips that to look at is to long to kiss.”2

Fred Barnard, illustration for chapter 46 of the Household Edition of Nicholas Nickleby (1875), detail. This illustration shows Madeline Bray taking care of her father.

Did Madeline choose the goblin-like Gride for her husband? No.

So why is she marrying him? Not for her own benefit, certainly. As Charles Dickens writes in Nicholas Nickleby, Madeline is the daughter of a debtor, a man who is confined within “the Rules of the Bench,” a neighborhood surrounding the King’s Bench debtor’s prison where debtors can reside as long as they do not leave. And Gride is the creditor who has confined him there. Gride offers to wipe out Bray’s debt and give him a small annuity in exchange for Bray’s persuading Madeline to marry him. Gride’s associate, Ralph Nickleby, urges Mr. Bray that even “men of family and fortune” often “marry their daughters to old men … to tickle some idle vanity, strengthen some family interest, or secure some seat in Parliament! Judge for her, sir, judge for her.”3 He also observes, about Gride, that Gride will “die soon, and leave her a rich young widow!”4

Ralph’s nephew implores Madeline not to go forward with the wedding with the accurate but devastating assessment that “You are betrayed and sold for money.”5

The Price of a Daughter

My previous two posts about not-Cinderella stories in Trollope and in the Sherlock Holmes canon focused on the ways in which the English laws of marriage and family provided incentives for prospective husbands and parents to fight for control over the money of an unmarried daughter. Dickens puts yet another spin on the unappealing marital choices available to young women: transactional approaches to marriage that amount, as Ralph’s nephew bluntly puts it, to a “sale for money” in which a parent offers a daughter to a prospective husband to obtain some financial benefit.

This plotline is based, not so much on legal considerations as on emotional ones: Dickens values above all else a loving daughter who is willing to sacrifice anything for the benefit of her father. As Gride himself observes to Ralph Nickleby, Madeline is “a slave to every wish of her only parent.“6 Indeed, Madeline is the archetype of Dickens’s self-erasing daughters. Although horror-stricken to the utmost at the prospect of marrying Gride, she agrees so that, as she says, “I can release my father who is dying in this place [the Rules of the Bench]; prolong his life, perhaps, for many years; restore him to comfort ….”7

How can you do it!

In Little Dorrit, Dickens presents an interesting variation on the story of the daughter willing to be offered up as a sacrifice for the sake of her father. That novel’s protagonist, Amy Dorrit, is the child of Frederick Dorrit, a gentleman who has been imprisoned at the Marshalsea debtors’ prison since before she was born. Raised in the prison, she maintains a sense of propriety and judgment that is continually tested by her family’s poverty. The novel movingly illustrates the degrading impact of the father’s imprisonment as he tries to maintain a veneer of gentility while begging for his subsistence.

Due to Mr. Dorrit’s prolonged residence at the prison and his genteel manners, he is treated well by the turnkeys. And when the son of one of the turnkeys, a young man named John Chivery, falls in love with Amy, both John and his father the turnkey are particularly attentive in bestowing favors upon Mr. Dorrit. Amy, who likes John – but does not love him – avoids him when she realizes that her father and the Chivery family have come to an implicit understanding that her father will bestow Amy upon John in exchange for continued favors and preferential treatment.

In a rare display of agency in a female Dickens protagonist, Amy refuses John when he approaches her and tells him never to ask again. And in her distress, she repeats to herself, “O dear, dear father, how can you, can you, do it!”8

J. Mahoney, illustration for Book the First, chapter 14 of the Household Edition of Little Dorrit (1873), detail. This shows Little Dorrit and her intellectually disabled friend Maggy after they have arrived late at the prison gate and been locked out. They spend the freezing night wandering around London.

Later, after Mr. Dorrit has learned of her rejection of John, he is discontented. He hints that “Something, I—hem!—I don’t know what, has gone wrong with Chivery [the father]. He is not—ha!—not nearly so obliging and attentive as usual to-night…. I am unfortunately dependent on these men for something every hour in the day.” He continues by observing that if he were to “lose the support and recognition of Chivery and his brother officers, I might starve to death here.” Eventually, he implies that Amy might “lead [John] on” or “tolerate him” “on her father’s … account.”9

I said above that Amy refuses John Chivery in a rare display of agency in a female Dickens protagonist, but that is not quite right. Although Amy spurns the sordid understanding between her father and Mr. Chivery, she does it as much for love of her father as from a desire to exercise her own independent will (although she is fortunate that her regard for her father and her inclinations as to prospective husbands point in the same direction). That is why she murmurs to herself, “O dear, dear father, how can you, can you, do it!” In refusing to play the game, she seeks to rescue her father from the degradation into which he is falling as he dangles her in front of the Chivery family in exchange for favors.

Sale and Shame

Fathers are not the only parents in Dickens’s novels to traffic (or attempt to traffic) their daughters for financial benefit. In Dombey and Son it is a mother, the elderly Mrs. Skewton, who regards her daughter, the queenly widow Edith Granger, as a means to gain an income. The two women eke out an existence at the lower rungs of gentility, maintaining appearances on a “small jointure” and “family connexions.” Mrs. Skewton understands that her best chance for escaping a life of genteel poverty is shopping Edith around to prospective new husbands capable of supporting not only Edith, but Mrs. Skewton as well. (The first marriage didn’t help their financial situation, because the husband died before coming into his money.)

As Edith bitterly puts it, “There is no slave in a market: there is no horse in a fair: so shown and offered and examined and paraded, Mother, as I have been …. I [have] been hawked and vended here and there, until the last grain of self-respect is dead within me, and I loathe myself.” She continues, “Take your own way, mother; share as you please in what you have gained; spend, enjoy, make much of it; and be as happy as you will.”10

Fred Barnard, illustration for chapter 36 of the Household Edition of Dombey and Son (1877), detail depicting Edith.

I won’t provide spoilers as to the fates of Madeline and Edith here, except to say that Edith’s not-Cinderella story ends in high drama, with a knife and a train. You have to read these novels to find out what happens!

Brief Appendix about the novels, all by Dickens, and a request for feedback and suggestions:

Nicholas Nickleby is an early novel featuring the titular hero, an endearing hothead, as he is cast, penniless, into the world upon the death of his father. The family of Wackford Squeers, the brutish Yorkshire schoolmaster to whom Nicholas is bound as an assistant, is a wonderful comic portrait, and there is moving criticism of the schools that were used to warehouse disabled or illegitimate children.

Little Dorrit is one of Dickens’s greatest novels, focusing on the impact of imprisonment, not just on Mr. Dorrit and Amy (as discussed above), but also on people who confine themselves emotionally. It is a fiery critique of the system of debtors’ prisons, the callousness of the rich, and the spirit of speculation that was sweeping Victorian England.

Dombey and Son is an underappreciated masterpiece, featuring Dickens’s most interesting female characters - not only Edith, but also the neglected daughter of Mr. Dombey. If any novel by Dickens could be called feminist, this would be it. This novel also addresses the tumultuous impact of the railways, which ran roughshod through urban neighborhoods, linked the city and the country, and created both new jobs and new hazards.

Here are the questions: what would you like to see me address in future posts? What should I be doing differently? You can comment here or privately message me in the Substack app with your responses, for which I will be extremely grateful.

Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby (1839), ch. 47.

Id.

Id.

Id., ch. 54.

Id., ch. 53.

Id., ch. 47.

Id., ch. 53.

Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit (1857), Book the First, ch. 18.

Id., ch. 19.

Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1848), ch. 27.

https://open.substack.com/pub/johnnogowski/p/did-dickens-recognize-his-breakthrough?r=7pf7u&utm_medium=ios

Hi Claire, do the fathers (or mothers) express remorse about forcing their daughters into these arrangements? Or was marriage considered so much on economic terms that they saw nothing wrong with pushing such undesirable husbands on their daughters?