“It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.”

What an epitaph. In addition to being one of the most moving endings I’ve ever read, these brief closing sentences of E.B. White’s 1952 novel Charlotte’s Web perfectly illuminate the book’s three great subjects: friendship, death – and writing.

Arthur Rackham, The Spider and the Fly, illustration for Aesop’s Fables (1912).

The invisible author

Wilbur is a newborn piglet, saved from death by a young girl, Fern, who throws herself in the way when her father is going to the pigpen to “do away with” the runt of the litter.1 A few months later, though, Wilbur learns from a wise old sheep that Fern’s intervention was only a stay of execution: the adults still plan to “turn [Wilbur] into smoked bacon and ham” once the cold weather comes. Wilbur panics: “I don’t want to die! Save me, somebody!”

The “somebody” who steps up is Wilbur’s new friend, the spider Charlotte. After much thought, she devises a rescue plan. One night, she weaves the words “SOME PIG” into her web.

Charlotte’s words have a profound impact on the humans who read them. Lurvy, the hired hand who first notices them, drops to his knees to pray. The farmer, Mr. Zuckerman, tells his wife that “a miracle has happened on this farm.” He tells her about the writing in the web and declares: “[W]e have a very unusual pig….”

Initially, Mrs. Zuckerman responds that “[W]e have no ordinary spider.” Mr. Zuckerman dismisses this idea: “It’s the pig that’s unusual. It says so, right there in the middle of the web.”2 The sight of the web soon convinces Mrs. Zuckerman that Wilbur, indeed, is “some pig.” As her initial skepticism dissolves, so too does her interest in the writer of the oracular message.

The news spreads. Everybody “from miles around” comes to gawk at Wilbur and read the web. And after seeing the writing, they affirm that they have “never seen such a pig before in their lives.”

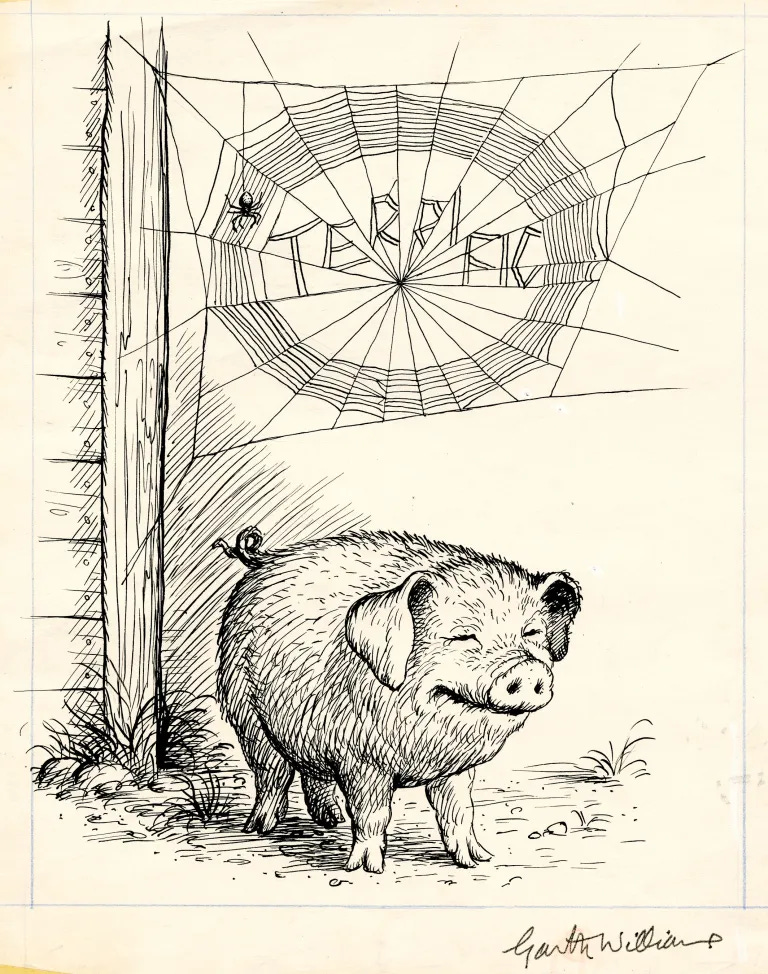

Every few days, Charlotte feels that she must devise fresh material to keep her audience engaged. So she casts about for words to replace “SOME PIG.” After consultation with the other animals, she writes new pronouncements: first “TERRIFIC,” then “RADIANT.” She rejects other suggestions such as “CRUNCHY” lest Zuckerman “start thinking about crisp, crunchy bacon.”

Garth Williams, illustration for Charlotte’s Web (1952), reproduced from Maria Popova, “E. B. White on Why He Wrote Charlotte’s Web, Plus His Rare Illustrated Manuscripts“ (The Marginalian, available here).

At the end of the summer, Charlotte accompanies Wilbur to the county fair, where she makes her final web and writes her last message about Wilbur: “HUMBLE.”

Each time Charlotte chooses a word, she, Wilbur, and the other animals consider whether Wilbur lives up to it. As they discuss “TERRIFIC,” Wilbur objects, “I’m not terrific, Charlotte. I’m just about average for a pig.” But Charlotte, fully understanding the power of writing, responds, “That doesn’t make a particle of difference …. People believe almost anything they see in print.”

The human readers are enchanted by Charlotte’s writing. As Mr. Zuckerman says, joyfully: “There isn’t a pig in the whole state that is as terrific as our pig.” He and others echo the words in the web throughout the novel.

At the fair, Wilbur is given “a special award” by the announcer:

“The fame of this unique animal has spread to the far corners of the earth …. Many of you will recall that never-to-be-forgotten day last summer when the writing appeared mysteriously on the spider’s web … calling the attention of all and sundry to the fact that this pig was completely out of the ordinary…. In the words of the spider’s web, ladies and gentlemen, this is some pig.”

Although Wilbur’s exceptionalism – entirely constructed by the words in the web – is universally recognized, “nobody notice[s] Charlotte.”

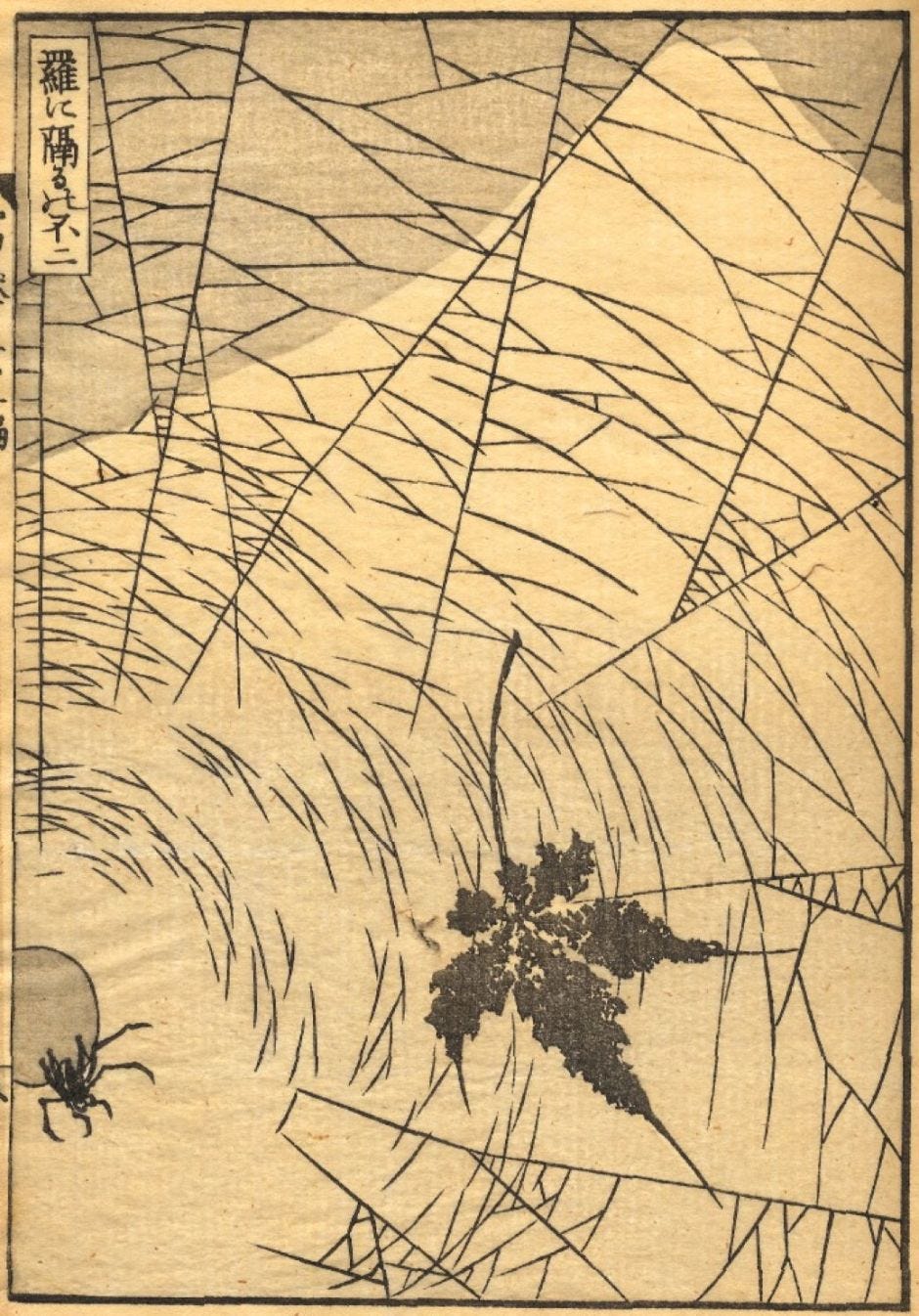

Hokusai (1760–1849), Mount Fuji Behind a Spider’s Web (date unknown).

Charlotte as prose stylist

While the story focuses on her writing, Charlotte is also a master wordsmith in speaking, an exemplar of the principles E.B. White was later to articulate in The Elements of Style.

When Charlotte first greets Wilbur with “salutations,” she is quick to edit herself. She explains: “When I say ‘salutations,’ it’s just my fancy way of saying hello or good morning. Actually, it’s a silly expression, and I am surprised that I used it at all.” (White’s suggestions in The Elements of Style include “Revise and rewrite” and “Avoid fancy words.”3) With other long-ish words, though, she explains them to Wilbur (“sedentary” means “I sit still a good part of the time”; “gullible” means “easy to fool”; “versatile” means not “full of eggs” as Wilbur suspects, but “turn[ing] with ease from one thing to another”).

Like most effective writers, Charlotte dislikes redundancy. Thus she complains about the triply repeated utterances of the geese: “Why can’t you just say ‘here’ [once]? Why do you have to repeat everything?” When one of the geese suggests, for a new message in the web, “How about ‘Terrific, terrific, terrific’?” Charlotte responds, “Cut that down to one ‘terrific’ and it will do very nicely.”4 Writing is powerful—if it’s good.

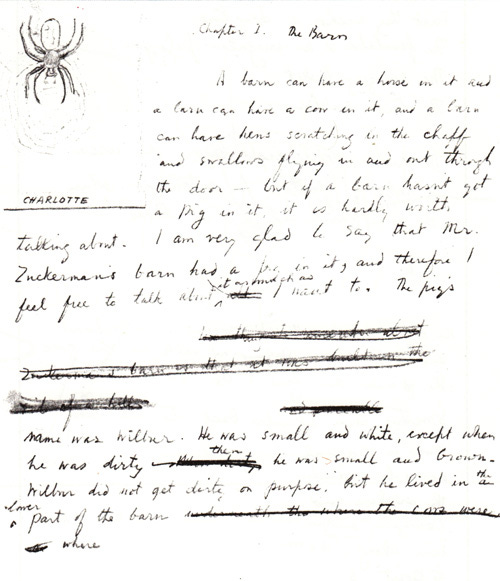

An early draft from E.B. White, with an excellent spider drawing. The draft itself is a testament to the importance of “revis[ing] and rewrit[ing]” — essentially none of what is written on this page made it into the published version, although we all should aspire to write as well as White did in this rejected draft. (Reproduced in Popova - see above.)

Writing in defiance of death

The sadness of the novel is that Charlotte’s life span is far shorter than Wilbur’s. Her death is foreshadowed by the crickets, who sing “the song of summer’s ending, a sad, monotonous song…. ‘Summer is dying, dying.’ … Even on the most beautiful days in the whole year – the days when summer is changing into fall – the crickets spread the rumor of sadness and change.”

As Charlotte nears her end, she reflects on her power as a writer. She remarks to Wilbur – far too humbly – that “Your success in the [fairground] ring this morning was, to a small degree, my success.” She even says, echoing the hopes of parents when talking to their children, “Maybe you’ll live forever – who knows?”5 In a sense, by the end of the novel, Charlotte has become Wilbur’s author – and she has written a new narrative arc for him.

As I’ve said before, I envision writing as a way – futile, no doubt – to cheat death, to project the writer’s consciousness beyond her end. Writing can be understood as creating a kind of permanence, or not-ending. But Charlotte’s writing is ephemeral. She destroys each word she writes in favor of the next. “SOME PIG” makes way for “TERRIFIC,” which Charlotte tears out in favor of “RADIANT.” At the last, “HUMBLE” is forgotten as Wilbur is loaded into his crate and Charlotte remains at the deserted fairgrounds to die alone. In all of her writing, she has been deliberately self-effacing to keep the attention on Wilbur. For Charlotte, writing is not a way to evade her own death, but to prevent an untimely death for Wilbur. As she says,

“Your future is assured…. You will live to enjoy the beauty of the frozen world, for you mean a great deal to Zuckerman and he will not harm you, ever. Winter will pass, the days will lengthen, the ice will melt in the pasture pond. The song sparrow will return and sing, the frogs will awake, the warm wind will blow again. All these sights and sounds and smells will be yours to enjoy, Wilbur – this lovely world, these precious days …”

While the writing in the web gives life to Wilbur, it gives meaning to Charlotte. She explains, “I wove my webs for you because I liked you. After all, what’s a life, anyway? We’re born, we live a little while, we die…. By helping you, perhaps I was trying to lift up my life a trifle.” This recognition of the brevity of life stands in contrast to her encouraging suggestion that “Maybe you’ll live forever.” The ephemerality of Charlotte’s webs reminds the reader that the wish to live forever is a wish never granted.

Charlotte’s Web falls within the didactic tradition practiced by writers such as Anthony Trollope, who believed that novels could not help but teach lessons to their readers. White affirmed the potency of the bond between writer and reader, asserting that reading has “a sublimity and power unequalled by any other form of communication.”6

White characterized Charlotte’s Web as “an appreciative story …. It celebrates life, the seasons, the goodness of the barn, the beauty of the world, the glory of everything.”7 It also illuminates the value of friendship and loyalty; the inevitability of death; – and the power of writing.

E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web (1952), p. 1. Given the brevity of the novel, I will not include page citations for quotations. They are easy enough to find and would be disruptive if sprinkled throughout the essay.

Id., p. 81 (emphasis added).

William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White, The Elements of Style (4th ed. 1979), p. 72 & p. 76.

White can’t resist including a few writing suggestions in addition to those conveyed by Charlotte. When the young girl Fern learns from her mother that Fern’s father is going to “do away with” the runty piglet, Fern provides an inadvertent lesson in avoiding euphemism by shrieking in response, “Do away with it? … You mean kill it? Just because it’s smaller than the others?” And when one of the lambs rudely tells Wilbur that “Pigs mean less than nothing to me,” Wilbur responds with a lesson in avoiding meaningless clichés: “What do you mean less than nothing? I don't think there is any such thing as less than nothing. Nothing is absolutely the limit of nothingness. It's the lowest you can go. It's the end of the line. How can something be less than nothing? If there were something that was less than nothing, then nothing would not be nothing, it would be something - even though it’s just a very little bit of something. But if nothing is nothing, then nothing has nothing that is less than it is.”

Templeton the rat plays the cynical realist in counterpoint to this when he sneers, “Who wants to live forever?”

E.B. White, “The Future of Reading,” in The New Yorker (March 2, 1951). Reprinted in Peter Neumeyer, The Annotated Charlotte’s Web (1994), p. 243. White went so far in this essay as to assert that “Reading is the work of the alert mind, is demanding, and under ideal conditions produces finally a sort of ecstasy. As in the sexual experience, there are never more than two persons present in the act of reading—the writer, who is the impregnator, and the reader, who is the respondent.”

Quoted in Phacharawan Boonpromkul, “Friendship, Humility, and the Complicated Morality of E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web,” in Manusya: Journal of Humanities 25: 1-18 (2022).

I remember holding back tears when reading Charlotte's Web to my children. I wanted them to recognize the sadness of Charlotte's death and the beauty of her gift to Wilbur without me leading them there. Plus mom shouldn't show up as a blubbering mess even if she feels like it.

I also appreciated Charlotte's stoicism. She clearly valued her life and her work but didn't make a fuss over it's end. It's good to be able to observe people (spiders!) dealing with tragedy and loss quietly.

So many wonderful children's books. I want to read them again just to myself.

Really insightful post, Claire. It reminds me of an old saying: when Cicero spoke people applauded, but when Demosthenes spoke they rioted. There is power in words, but it's hard to harness. It's much easier to use them to make people angry enough to throw things... or even to get people to off themselves, as ancient Greek Archilochus did when he wrote a humiliating play about a former lover who spurned him (she called him a "bastard", which he probably was in every sense). But it's harder to use words to get people to see magic and wonder. Or to see the beauty and "terrific-ness" of the mundane things that surround us. It's like the world is full of magic and we don't realize it!